Uranium Boom and Plutonium Bust: Russia, Japan, China and the World

Peter LeeOver the last decade, the world of fissionable material has experienced a quiet revolution. Plutonium, once the lethal darling of nations seeking a secure source of fuel for their nuclear reactors (and their nuclear weapons) has fallen from favor. Uranium has replaced plutonium as the feedstock of choice for the world’s nuclear haves. And business is booming.

Asian powers like China and India, concerned about energy security and environmental degradation—and despite the disaster at Fukushima—are turning to nuclear power. The demand for uranium is expected to grow by over 40% over the next five years.

The Australian - Global Uranium Demand Expected To Skyrocket

In an unexpected but, in retrospect, logical development, Russia is emerging as the dominant global player in the nuclear fuel industry, with the apparent acquiescence of the United States. Today, as Russia sheds some of its bloated Soviet-era nuclear arsenal, it ships legacy plutonium to the United States to provide almost half of the fuel burned in American nuclear plants. At the same time, the Russian government is moving aggressively to establish its state-run nuclear corporation, ARMZ, as a dominant player in the worldwide rush to increase uranium production.

Russia brings some unique advantages to the nuclear fuel business. The first is an impressive stockpile of excess plutonium. This, however, is a wasting asset as Russia works through its current inventory without generating significant new quantities of metal. Russia is keeping its fingers in the plutonium pot through a program of constructing fast breeder reactors—which generate a surplus of plutonium—despite their technical, safety, and cost headaches.

The second and most crucial advantage is what one might characterize as a determinedly cavalier attitude toward the hazards of nuclear waste, reinforced by the fact that Russia is already a nightmare of nuclear contamination. In fact, it is possible that any additional shipments of nuclear waste to Russia will not contribute significantly to the already dire state of affairs.

Nuclear waste is unpopular, as the successful effort to block the US disposal facility at Yucca Mountain attests. Russia’s ability to absorb it—despite growing anxiety and activism within the country—is a major competitive advantage. Countries and companies that burn nuclear fuel but have no local recourse except on-site storage are naturally interested—and sometimes legally compelled—to source their material from a supplier that is willing to accept and dispose of the waste.

Russia—even though its domestic uranium reserves are rather paltry—has become a major player in uranium production through investments in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and other nations. Mr. Putin and the Russian government has played geopolitical hardball in order to improve the competitive position of its ARMZ Uranium Holding Company, as the Mongolian example discussed below demonstrates.

Russia’s pivot toward uranium can be contrasted instructively with Japan’s. Plutonium can be regarded as one of Japan’s biggest misplaced industrial policy bets. As a very interesting article by Joseph Trento of the investigative organization National Security News Service, reveals, in the 1970s the Japanese government decided that Japan had to have a closed nuclear fuel cycle, in which plutonium would be generated in significant amounts in fast breeder reactors, extracted from spent nuclear fuel, and funneled back into Japanese nuclear power plants.

DC Bureau - United States Circumvented Laws To Help Japan Accumulate Tons Of Plutonium

The ostensible motivation for this policy was the scarcity of the uranium alternative. Nowadays, when uranium reserves are turning up on every continent (and, in the case of Kazakhstan, low-assay ores are processed in situ economically, if not particularly attractively, with a dousing of injected acid and recovered), it is difficult to recall that the dominant perception in the last century was of a uranium shortage.

The Japanese government declared it did not want to substitute uranium import dependence for hydrocarbon dependence, and it wanted to establish its nuclear power industry on the basis of breeder reactors creating plutonium and processing plants separating out the metal for fabrication into fuel—a closed cycle that would render Japan self-sufficient in nuclear material.

It appears that Japan also had two less apparent, or at least less-publicized, motives.

The first was to give Japanese industry—specifically Mitsubishi Heavy Industries—a leg-up in becoming a dominant global force in supplying fast-breeder technology and equipment, a process that was expected to dominate civilian nuclear power generation in the 21st century since it produced more nuclear fuel than it burned.

The second was to generate a reassuring pile of weapons-grade plutonium at a time when the United States was cozying up to a nuclear-capable China as a counterweight to the USSR, and Japan had to confront the possibility that it might be left to find its own security/defense way in the Pacific region.

This effort required US technical assistance. The deal was done with the Reagan administration in a sweetheart arrangement along the lines of what the Bush and Obama administrations gave this century’s anti-Communist counterweight, India. Unlike other nations, Japan could dispose of its plutonium-rich waste at its own discretion.

Japan embarked on a major nuclear energy program and generated sizable quantities of nuclear waste. At the same time, the Japanese government poured billions of dollars into fast breeder and reprocessing projects based on US technology that yielded few tangible results and some genuine nuclear hazard scares, such as the cooling system leak that occurred in at the experimental breeder reactor facility at Monju in 1995 and shut down the facility for 14 years.

Monju |

Jan-Feb 2010 Citizen's Nuclear Information Newsletter

Despite a 2006 government report estimating that the cost of reprocessing spent nuclear fuel over the next 40 years would amount to 18 trillion yen, the Japanese energy establishment appears to be in the grip of political and technological inertia and is still proceeding with its program (although non-proliferation expert Frank von Hippel pointed out that mothballing the Rokkasho plant would still provide ample jobs “for decades” for the adjacent village: decontamination expenses related to the current storage operations alone would amount to 1.5 trillion yen).

Japan's Spent Fuel and Plutonium Management Challenges - Katsuda & Suzuki

Kyodo News// Opinion - "Reconsidering the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant

Without viable local processing capability, Japan stored some of its waste in cooling ponds on site (such as in the cooling ponds now bedeviling Fukushima), at Rokkasho, and at an interim storage facility. The rest is shipped to France and Great Britain, the only two countries that still maintain a reprocessing capability.

Now, despite a stated policy of no surplus plutonium, Japan is the proud owner of an estimated 46 tons of plutonium—ten tons of it in country, the rest of it held by France and Great Britain on its behalf. If Rokkasho operates as planned, Japan’s total plutonium stock would triple by 2020.

For comparison purposes, China is estimated to hold less than 20 tons of highly enriched uranium and a small amount of plutonium. The PRC has probably not produced any weapons-grade fissile material since 1990.

Tehelka - the secret of India's nuke stocks is out

While the world wrings its hands over Iran and its 15 pounds of highly enriched uranium, Japan appears the more pressing nuclear weapon breakout threat.

CNS - civil highly enriched uranium: who has what?

A focus of US diplomacy is keeping the Japanese nuclear weapons dragon bottled up. A weaponized Japan, in addition to generating a certain amount of regional anxiety and triggering an arms race, could turn into an Israel of the Pacific i.e. a titular US ally but with its own security policy more beholden to national interests, fears, and politics than US strategic priorities.

Not unsurprisingly, South Korea, surrounded by actual and potential nuclear weapons states, is trying to go the spent fuel reprocessing route, but has, at least for now been rebuffed by the United States. After the current US-Korea nuclear treaty expires in 2014—and the US will still be unable to offer South Korea any spent fuel storage options—it remains to be seen how firm US resolve will remain.

South Korean Reprocessing: An Unnecessary Threat to the Nonproliferation Regime

Overall, today, the world finds itself in a situation in which plutonium is passé and uranium is de rigeur.

Russia continues to build breeder reactors as part of its nuclear portfolio but has shifted its focus to uranium. China operates a small experimental program. India runs a big unit to generate plutonium for its weapons program. And, there’s Japan. That’s about it.

The US, France, and UK have all shut down their breeder reactors. The UK is considering a shutdown of its Sellafield processing facility because of slackened demand, and is looking at ways to burn weapons-grade nuclear fuel directly into a reactor.

Uranium brings its own matrix of advantages and headaches. Not only is uranium ore relatively plentiful, improvements in centrifuging allow it to be enriched to fuel and weapons grade in a relatively efficient and elegant way compared to the massive diffusion plants that were the norm at Oak Ridge during the 1940s and 1950s.

Perhaps it has become too cheap and easy to pursue the uranium route, as the examples of Pakistan, Libya, Iran, and North Korea imply.

Non-proliferation, instead of relying on the technical and financial barriers erected by the fiendish complexities of generating, separating, and refining plutonium metal or gaseous diffusion of uranium hexafluoride, must turn to the use of sanctions and sabotage (such as the Stuxnet worm) to deter unwelcome actors.

And the general eagerness to advance the commercial development of the nuclear industry has placed Russia—hardly a reliable or benevolent partner of the West—near the center of the world uranium industry with a vested strategic and economic industry in promoting its expansion.

In the case of Iran, a prime customer for Russian nuclear technology and fuel, Moscow is clearly going beyond business imperatives acting in the service of geostrategic calculations that the United States and its allies decidedly do not share.

Meanwhile, Iran’s neighbors such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey pursue nuclear energy agreements with Russian and Chinese support. In the Saudi case, Prince Faisal bluntly stated that the Kingdom is interested in nuclear weapons, not just nuclear power.

Saudi Arabia may seek nuclear weapons prince says.

With the decline of plutonium, the proliferation dangers of nuclear energy have not ended. They have simply mutated in response to the new commercial and technological imperatives of the uranium industry.

Peter Lee writes on East and South Asian affairs and their intersection with US global policy. He is the moving force behind the Asian affairs website China Matters which provides continuing critical updates on China and Asia-Pacific policies. His work frequently appears at Asia Times.

Appendix, Mainichi Shimbun,

Mongolia’s Secret Plan for an International Nuclear Waste Disposal Site

Aikawa HaruyukiThe secret plan surfaced as the crisis at the tsunami-hit Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant has stirred controversy over the pros and cons of nuclear power.

I learned that the Japanese Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry and the U.S. Department of Energy had been secretly negotiating the plan with Mongolia since the autumn of 2010 when I interviewed a U.S. nuclear expert on the phone on April 9, 2011.

"Would you please help the Mongolian people who know nothing about the plan. Mongolia is friendly to Japan, Japanese media certainly has influence on the country," the expert said.

I flew to Ulan Bator, the capital of Mongolia, on April 22, and met with then Ambassador Undraa Agvaanluvsan with the Mongolian Foreign Ministry in charge of negotiations on the plan, at the VIP room of a cafe.

Before I asked the ambassador some questions getting to the heart of the plan, we asked my interpreter to leave the room just as we had agreed in advance. The way the ambassador talked suddenly became more flexible after I stopped the recorder and began asking her questions in English. She explained the process and the aim of the negotiations and even mentioned candidate sites for the disposal facility.

After the interview that lasted for more than two hours, the ambassador said she heard of a similar plan in Australia and asked me to provide Mongolia with any information on it, highlighting the Mongolian government's enthusiasm about overcoming competition with Australia in hosting the disposal facility.

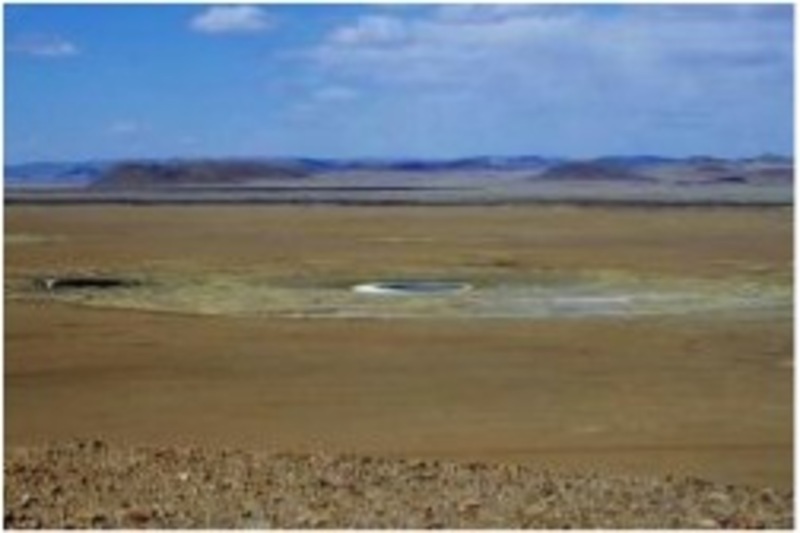

I subsequently visited three areas where the Mongolian government was planning to build nuclear power stations. Japan and the United States were to provide nuclear power technology to Mongolia in return for hosting the disposal facility. I relied on a global positioning system for driving in the vast, grassy land to head to the sites. All the three candidate sites, including a former air force base about 200 kilometers southeast of Ulan Bator, are all dry land. No source of water indispensable for cooling down nuclear reactors, was found at any of these sites and a lake at one of the sites had dried up.

Experts share the view that nuclear plants cannot be built in areas without water. I repeatedly asked Mongolian officials responsible for nuclear power policy how they can build nuclear plants at the sites without water. However, they only emphasized that all the three sites meet the safety standards for nuclear plants set by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

An Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry official, who is familiar with Mongolian affairs, said, "Mongolians are smart but their knowledge of atomic energy isn't that good ..."

In other words, Japan and the United States proposed to build a spent nuclear waste disposal facility in Mongolia, a country that has little knowledge of nuclear energy.

In 2010, the administration of then Prime Minister Kan Naoto released a new growth strategy with special emphasis on exports of nuclear power plants. However, there is no facility in Japan that can accept spent nuclear fuel, putting itself at a disadvantage in its competition with Russia, France and other countries that have offered to sell nuclear plants and accept radioactive waste as a package. A Japanese negotiator said, "The plan to build a disposal facility in Mongolia was aimed at making up for our disadvantage in selling nuclear power stations."

The United States wanted to find another country that will accept spent nuclear fuel that can be converted to materials to develop nuclear weapons in a bid to promote its nuclear non-proliferation policy.

Both the Japanese and U.S. ideas are understandable. However, as Mongolia has just begun developing uranium mines and has not benefited from atomic energy, I felt that it would be unreasonable to shift radioactive waste to Mongolia without explaining the plan to the Mongolian people.

During my stay in Mongolia, I learned that many people there donated money equal to their daily wages to victims of the March 11, 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. I was also present when the Mongolian people invited disaster evacuees from Miyagi Prefecture to their country. I could not help but shed tears when seeing the Mongolian people's goodwill. My interpreter even joked, "You cry too much."

I did not feel a sense of exaltation from learning the details of the secret negotiations on the disposal site. I rather felt ashamed of being a citizen of Japan, which was promoting the plan.

The Fukushima nuclear crisis that broke out following the March 11, 2011 quake and tsunami has sparked debate on overall energy policy. Some call for an immediate halt to nuclear plants while others insist that such power stations are indispensable for Japan's overall energy, industrial and security policies.

"The matter isn't limited to nuclear energy. Our generations have consumed massive amounts of oil and coal," a Finish government official said.

The Mainichi scoop on the secret plan sparked campaigns in Mongolia to demand that the plan on a spent nuclear fuel disposal facility be scrapped and that relevant information be fully disclosed.

Bowing to the opposition, Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj declared in the U.N. General Assembly session in September last year that the country can never host a radioactive waste disposal facility.

Amano Yukiya, director general of the IAEA, which is dubbed a "nuclear watchdog," says, "Those who generate radioactive waste must take responsibility for disposing of it. It's unfair to expect someone else to take care of it."

However, human beings have yet to find a solution to problems involving nuclear waste.

Aikawa Haruyuki, Europe General Bureau, Mainichi Shimbun

(Mainichi Japan) March 13, 2012

Click [here] for the original Japanese story.

Click [here] for the original English : Mainichi scoop on Mongolia's nuclear plans highlights problems in dealing with waste.

Recommended citation: Peter Lee, "Uranium Boom and Plutonium Bust: Russia, Japan, China and the World," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 18, No. 1.

Articles on related subjects

• Peter Hayes, Global Perspectives on Nuclear Safety and Security After 3-11 [here]

• Peter Lee, A New ARMZ Race: The Road to Russian Uranium Monopoly Leads Through Mongolia [here]

• Miles Pomper, Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, Stephanie Lieggi, and Lawrence Scheinman, Nuclear Power and Spent Fuel in East Asia: Balancing Energy, Politics and Nonproliferation [here]

• Richard Tanter, Arabella Imhoff and David Von Hippel, Nuclear Power, Risk Management and Democratic Accountability in Indonesia: Volcanic, regulatory and financial risk in the Muria peninsula nuclear power proposal [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Sino-Russian Alliance Comes of Age: Geopolitics and Energy Politics [here]

• Geoffrey Gunn, Southeast Asia’s Looming Nuclear Power Industry [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Russia, Iran and Eurasian Energy Politics [here]

- See more at: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Peter-Lee/3743#sthash.tDYHK83w.dpuf

Uranium Boom and

Plutonium Bust: Russia, Japan, China and the World

Peter Lee

http://www.japanfocus.org/-Peter-Lee/3743

Over the last decade, the world of fissionable

material has experienced a quiet revolution. Plutonium, once the lethal darling

of nations seeking a secure source of fuel for their nuclear reactors (and

their nuclear weapons) has fallen from favor. Uranium has replaced plutonium as

the feedstock of choice for the world’s nuclear haves. And business is booming.

Asian powers like China

and India, concerned about

energy security and environmental degradation—and despite the disaster at Fukushima—are turning to

nuclear power. The demand for uranium is expected to grow by over 40%

over the next five years.

The

Australian - Global Uranium Demand Expected To Skyrocket

In an unexpected but, in retrospect, logical

development, Russia is

emerging as the dominant global player in the nuclear fuel industry, with the

apparent acquiescence of the United

States. Today, as Russia

sheds some of its bloated Soviet-era nuclear arsenal, it ships legacy plutonium

to the United States

to provide almost half of the fuel burned in American nuclear plants. At the

same time, the Russian government is moving aggressively to establish its

state-run nuclear corporation, ARMZ, as a dominant player in the worldwide rush

to increase uranium production.

Russia

brings some unique advantages to the nuclear fuel business. The first is an

impressive stockpile of excess plutonium. This, however, is a wasting

asset as Russia

works through its current inventory without generating significant new

quantities of metal. Russia

is keeping its fingers in the plutonium pot through a program of constructing

fast breeder reactors—which generate a surplus of plutonium—despite their

technical, safety, and cost headaches.

The second and most crucial advantage is what one

might characterize as a determinedly cavalier attitude toward the hazards of

nuclear waste, reinforced by the fact that Russia is already a nightmare of

nuclear contamination. In fact, it is possible that any additional

shipments of nuclear waste to Russia

will not contribute significantly to the already dire state of affairs.

Nuclear waste is unpopular, as the successful

effort to block the US

disposal facility at Yucca

Mountain attests. Russia’s

ability to absorb it—despite growing anxiety and activism within the country—is

a major competitive advantage. Countries and companies that burn nuclear

fuel but have no local recourse except on-site storage are naturally

interested—and sometimes legally compelled—to source their material from a

supplier that is willing to accept and dispose of the waste.

Russia—even though its domestic uranium reserves

are rather paltry—has become a major player in uranium production through

investments in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and other nations. Mr. Putin and the

Russian government has played geopolitical hardball in order to improve

the competitive position of its ARMZ Uranium Holding Company, as the Mongolian

example discussed below demonstrates.

Russia’s

pivot toward uranium can be contrasted instructively with Japan’s.

Plutonium can be regarded as one of Japan’s biggest misplaced

industrial policy bets. As a very interesting article by Joseph Trento of the

investigative organization National Security News Service, reveals, in the

1970s the Japanese government decided that Japan had to have a closed nuclear

fuel cycle, in which plutonium would be generated in significant amounts in

fast breeder reactors, extracted from spent nuclear fuel, and funneled back

into Japanese nuclear power plants.

The ostensible motivation for this policy was the

scarcity of the uranium alternative. Nowadays, when uranium reserves are

turning up on every continent (and, in the case of Kazakhstan, low-assay ores are

processed in situ economically, if not particularly attractively, with a

dousing of injected acid and recovered), it is difficult to recall that the

dominant perception in the last century was of a uranium shortage.

The Japanese government declared it did not want

to substitute uranium import dependence for hydrocarbon dependence, and it

wanted to establish its nuclear power industry on the basis of breeder reactors

creating plutonium and processing plants separating out the metal for

fabrication into fuel—a closed cycle that would render Japan self-sufficient in

nuclear material.

It appears that Japan also had two less apparent,

or at least less-publicized, motives.

The first was to give Japanese

industry—specifically Mitsubishi Heavy Industries—a leg-up in becoming a

dominant global force in supplying fast-breeder technology and equipment, a

process that was expected to dominate civilian nuclear power generation in the

21st century since it produced more nuclear fuel than it burned.

The second was to generate a reassuring pile of

weapons-grade plutonium at a time when the United

States was cozying up to a nuclear-capable China as a counterweight to the USSR, and Japan had to confront the

possibility that it might be left to find its own security/defense way in the

Pacific region.

This effort required US technical assistance. The

deal was done with the Reagan administration in a sweetheart arrangement along

the lines of what the Bush and Obama administrations gave this century’s

anti-Communist counterweight, India.

Unlike other nations, Japan

could dispose of its plutonium-rich waste at its own discretion.

Japan

embarked on a major nuclear energy program and generated sizable quantities of

nuclear waste. At the same time, the Japanese government poured billions

of dollars into fast breeder and reprocessing projects based on US technology

that yielded few tangible results and some genuine nuclear hazard scares, such

as the cooling system leak that occurred in at the experimental breeder reactor

facility at Monju in 1995 and shut down the facility for 14 years.

Monju

Japan’s

two trillion yen spent fuel reprocessing facility at Rokkasho, a sister to the

mammoth operations at Sellafield in the UK

and Le Havre in France, has experienced a series of

startup problems and has not yet entered production.

Despite a 2006 government report estimating that

the cost of reprocessing spent nuclear fuel over the next 40 years would amount

to 18 trillion yen, the Japanese energy establishment appears to be in the grip

of political and technological inertia and is still proceeding with its program

(although non-proliferation expert Frank von Hippel pointed out that

mothballing the Rokkasho plant would still provide ample jobs “for decades” for

the adjacent village: decontamination expenses related to the current storage

operations alone would amount to 1.5 trillion yen).

Japan's

Spent Fuel and Plutonium Management Challenges - Katsuda & Suzuki

Without viable local processing capability, Japan stored some of its waste in cooling ponds

on site (such as in the cooling ponds now bedeviling Fukushima), at Rokkasho, and at an interim

storage facility. The rest is shipped to France

and Great Britain,

the only two countries that still maintain a reprocessing capability.

Now, despite a stated policy of no surplus

plutonium, Japan is the

proud owner of an estimated 46 tons of plutonium—ten tons of it in country, the

rest of it held by France

and Great Britain

on its behalf. If Rokkasho operates as planned, Japan’s total plutonium stock would

triple by 2020.

For comparison purposes, China is

estimated to hold less than 20 tons of highly enriched uranium and a small

amount of plutonium. The PRC has probably not produced any weapons-grade

fissile material since 1990.

While the world wrings its hands over Iran and its 15 pounds of highly enriched

uranium, Japan

appears the more pressing nuclear weapon breakout threat.

A focus of US diplomacy is keeping the

Japanese nuclear weapons dragon bottled up. A weaponized Japan, in addition to generating a certain

amount of regional anxiety and triggering an arms race, could turn into an Israel of the

Pacific i.e. a titular US ally but with its own security policy more beholden

to national interests, fears, and politics than US strategic priorities.

Not unsurprisingly, South

Korea, surrounded by actual and potential nuclear weapons

states, is trying to go the spent fuel reprocessing route, but has, at least

for now been rebuffed by the United

States. After the current US-Korea

nuclear treaty expires in 2014—and the US will still be unable to offer South

Korea any spent fuel storage options—it remains to be seen how firm US resolve

will remain.

Overall, today, the world finds itself in a

situation in which plutonium is passé and uranium is de rigeur.

Russia

continues to build breeder reactors as part of its nuclear portfolio but has

shifted its focus to uranium. China operates a small experimental

program. India

runs a big unit to generate plutonium for its weapons program. And,

there’s Japan.

That’s about it.

The US, France,

and UK

have all shut down their breeder reactors. The UK is considering a shutdown of its

Sellafield processing facility because of slackened demand, and is looking at

ways to burn weapons-grade nuclear fuel directly into a reactor.

Uranium brings its own matrix of advantages and

headaches. Not only is uranium ore relatively plentiful, improvements in

centrifuging allow it to be enriched to fuel and weapons grade in a relatively

efficient and elegant way compared to the massive diffusion plants that were

the norm at Oak Ridge during the 1940s and 1950s.

Perhaps it has become too cheap and easy to

pursue the uranium route, as the examples of Pakistan,

Libya, Iran, and North Korea imply.

Non-proliferation, instead of relying on the

technical and financial barriers erected by the fiendish complexities of

generating, separating, and refining plutonium metal or gaseous diffusion of

uranium hexafluoride, must turn to the use of sanctions and sabotage (such as

the Stuxnet worm) to deter unwelcome actors.

And the general eagerness to advance the

commercial development of the nuclear industry has placed Russia—hardly a

reliable or benevolent partner of the West—near the center of the world uranium

industry with a vested strategic and economic industry in promoting its

expansion.

In the case of Iran,

a prime customer for Russian nuclear technology and fuel, Moscow

is clearly going beyond business imperatives acting in the service of

geostrategic calculations that the United States and its allies

decidedly do not share.

Meanwhile, Iran’s

neighbors such as Saudi Arabia

and Turkey

pursue nuclear energy agreements with Russian and Chinese support. In the

Saudi case, Prince Faisal bluntly stated that the Kingdom is interested in

nuclear weapons, not just nuclear power.

With the decline of plutonium, the proliferation

dangers of nuclear energy have not ended. They have simply mutated in

response to the new commercial and technological imperatives of the uranium

industry.

Peter Lee writes on East and

South Asian affairs and their intersection with US global policy. He is the moving

force behind the Asian affairs website China Matters which provides

continuing critical updates on China

and Asia-Pacific policies. His work frequently appears at Asia Times.

Appendix, Mainichi Shimbun,

Mongolia’s Secret Plan for an International

Nuclear Waste Disposal Site

Aikawa Haruyuki

One

of the candidate sites for a nuclear power plant in Mongolia is

pictured in April 2011. There is no source of water needed to cool down

reactors as the lake in the center of the photo has dried up. (Mainichi)

Coverage on a secret document detailing an

international nuclear waste disposal site that Japan

and the United States had

planned to build in Mongolia,

for which I won the Vaughan-Ueda Memorial Prize for 2011, has highlighted the

difficulties in dealing with radioactive waste.

The secret plan surfaced as the crisis at the

tsunami-hit Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant has stirred controversy over

the pros and cons of nuclear power.

I learned that the Japanese Economy, Trade and

Industry Ministry and the U.S. Department of Energy had been secretly

negotiating the plan with Mongolia

since the autumn of 2010 when I interviewed a U.S. nuclear expert on the phone on

April 9, 2011.

"Would you please help the Mongolian people

who know nothing about the plan. Mongolia

is friendly to Japan,

Japanese media certainly has influence on the country," the expert said.

I flew to Ulan Bator,

the capital of Mongolia,

on April 22, and met with then Ambassador Undraa Agvaanluvsan with the

Mongolian Foreign Ministry in charge of negotiations on the plan, at the VIP

room of a cafe.

Before I asked the ambassador some questions

getting to the heart of the plan, we asked my interpreter to leave the room

just as we had agreed in advance. The way the ambassador talked suddenly became

more flexible after I stopped the recorder and began asking her questions in

English. She explained the process and the aim of the negotiations and even

mentioned candidate sites for the disposal facility.

After the interview that lasted for more than two

hours, the ambassador said she heard of a similar plan in Australia and asked me to provide Mongolia with any information on it,

highlighting the Mongolian government's enthusiasm about overcoming competition

with Australia

in hosting the disposal facility.

I subsequently visited three areas where the

Mongolian government was planning to build nuclear power stations. Japan and the United

States were to provide nuclear power technology to Mongolia in

return for hosting the disposal facility. I relied on a global positioning

system for driving in the vast, grassy land to head to the sites. All the three

candidate sites, including a former air force base about 200 kilometers

southeast of Ulan Bator,

are all dry land. No source of water indispensable for cooling down nuclear

reactors, was found at any of these sites and a lake at one of the sites had

dried up.

Experts share the view that nuclear plants cannot

be built in areas without water. I repeatedly asked Mongolian officials

responsible for nuclear power policy how they can build nuclear plants at the

sites without water. However, they only emphasized that all the three sites

meet the safety standards for nuclear plants set by the International Atomic

Energy Agency (IAEA).

An Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry official,

who is familiar with Mongolian affairs, said, "Mongolians are smart but

their knowledge of atomic energy isn't that good ..."

In other words, Japan

and the United States

proposed to build a spent nuclear waste disposal facility in Mongolia, a

country that has little knowledge of nuclear energy.

In 2010, the administration of then Prime

Minister Kan Naoto released a new growth strategy with special emphasis on

exports of nuclear power plants. However, there is no facility in Japan that can accept spent nuclear fuel,

putting itself at a disadvantage in its competition with Russia, France and other countries that

have offered to sell nuclear plants and accept radioactive waste as a package.

A Japanese negotiator said, "The plan to build a disposal facility in Mongolia was

aimed at making up for our disadvantage in selling nuclear power

stations."

The United States wanted to find

another country that will accept spent nuclear fuel that can be converted to

materials to develop nuclear weapons in a bid to promote its nuclear

non-proliferation policy.

Both the Japanese and U.S. ideas are understandable.

However, as Mongolia has

just begun developing uranium mines and has not benefited from atomic energy, I

felt that it would be unreasonable to shift radioactive waste to Mongolia

without explaining the plan to the Mongolian people.

During my stay in Mongolia, I learned that many

people there donated money equal to their daily wages to victims of the March

11, 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. I was also present when the Mongolian

people invited disaster evacuees from Miyagi Prefecture

to their country. I could not help but shed tears when seeing the Mongolian

people's goodwill. My interpreter even joked, "You cry too much."

I did not feel a sense of exaltation from

learning the details of the secret negotiations on the disposal site. I rather

felt ashamed of being a citizen of Japan, which was promoting the

plan.

The Fukushima

nuclear crisis that broke out following the March 11, 2011 quake and tsunami

has sparked debate on overall energy policy. Some call for an immediate halt to

nuclear plants while others insist that such power stations are indispensable

for Japan's

overall energy, industrial and security policies.

"The matter isn't limited to nuclear energy.

Our generations have consumed massive amounts of oil and coal," a Finish

government official said.

The Mainichi scoop on the secret plan sparked

campaigns in Mongolia

to demand that the plan on a spent nuclear fuel disposal facility be scrapped

and that relevant information be fully disclosed.

Bowing to the opposition, Mongolian President

Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj declared in the U.N. General Assembly session in

September last year that the country can never host a radioactive waste

disposal facility.

Amano Yukiya, director general of the IAEA, which

is dubbed a "nuclear watchdog," says, "Those who generate

radioactive waste must take responsibility for disposing of it. It's unfair to

expect someone else to take care of it."

However, human beings have yet to find a solution

to problems involving nuclear waste.

Aikawa Haruyuki, Europe General Bureau, Mainichi Shimbun

(Mainichi Japan)

March 13, 2012

Click [here]

for the original Japanese story.

Click [here]

for the original English : Mainichi scoop on Mongolia's nuclear plans highlights

problems in dealing with waste.

Recommended

citation: Peter Lee,

"Uranium Boom and Plutonium Bust: Russia,

Japan, China and the

World," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 18, No. 1.

Articles on

related subjects

• Peter Hayes,

Global Perspectives on Nuclear Safety and Security After 3-11 [here]

• Peter Lee, A New

ARMZ Race: The Road to Russian Uranium Monopoly Leads Through Mongolia [here]

• Miles Pomper,

Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, Stephanie Lieggi, and Lawrence Scheinman, Nuclear Power

and Spent Fuel in East Asia: Balancing Energy, Politics and Nonproliferation [here]

• Richard Tanter,

Arabella Imhoff and David Von Hippel, Nuclear Power, Risk Management and

Democratic Accountability in Indonesia: Volcanic, regulatory and financial risk

in the Muria peninsula nuclear power proposal [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar,

Sino-Russian Alliance Comes of Age: Geopolitics and Energy Politics [here]

• Geoffrey Gunn, Southeast Asia’s Looming Nuclear Power Industry [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Russia, Iran and Eurasian Energy

Politics [here]

-

See more at: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Peter-Lee/3743#sthash.tDYHK83w.dpuf

The Australian - Global Uranium Demand Expected To Skyrocket

Monju

One

of the candidate sites for a nuclear power plant in Mongolia is

pictured in April 2011. There is no source of water needed to cool down

reactors as the lake in the center of the photo has dried up. (Mainichi)

Uranium Still Booming

$100/pound should come sooner than anticipated

By Keith Kohl

http://www.goldworld.com/articles/uranium-profit-investing/126

Baltimore,

MD - After uranium's record price jump this week, it looks like $100

per pound will come sooner than anticipated. And if you haven't

established yourself in this bullish trend, you may want to reconsider

your position.

Follow the Yellow Brick Road . . .

The spot price for uranium oxide jumped another $6 this week, hitting

$91 per pound. The increase was spurred by consistent supply

shortfalls. The world's roughly 440 nuclear reactors need well over 150

million pounds of uranium every year.

So how much uranium do we currently produce?

Only about 100 million pounds. And the stockpile of uranium collected from disassembled nuclear weapons is declining fast.

To say the least, uranium is currently in a huge bull market - just look at price soar since 2003:

This means the price of uranium has risen over 810% in four years!

The burgeoning nuclear industry has contributed to the tight supplies. And the emerging global energy crisis has thrown nuclear energy into the spotlight. While a few alternative energy sources are making headway, future global demand will require energy on a vast scale - something nuclear power can provide.

Consider these facts from the World Nuclear Association Symposium in 2001:

· 1 kg of firewood equals about 1 kWh of electricity

· 1 kg of coal or oil equals roughly 3 or 4 kWh of electricity.

· But 1 kg of natural uranium equals nearly 50,000 kWh of electricity!

Yet the spread of nuclear technology hasn't been the only factor in boosting uranium's price.Flooding Profits

Natural disasters are never a laughing matter, especially when the devastating impact is widely felt.

But they're much easier to cope with when they give you unprecedented financial gains.

Losing the world's largest undeveloped high-grade uranium project dealt a huge blow to uranium production. Before it flooded, Cameco's Cigar Lake operation was expected to produce about 18 million pounds of uranium annually. The mine would have supplied more than 10% of the world's current uranium demand.

Yet the flood in October makes for a shaky future. There is a possibility that the mine will be lost altogether. Next month, Cameco will release an updated report assessing the situation at Cigar Lake.

Even the best-case scenario would mean postponing production until 2008.

Play with the Big Boys

So it's too late to profit from this bull, right?

Trust me, that couldn't be further from the truth.

The Middle East may know about oil, but when it comes to uranium, the only choices for investment are either Canada or Australia. Together, those two make up roughly 45% of the world's uranium production.

And with such a shortfall in supply, the chances for tiny exploration companies to post tenfold profits are excellent.

One of the best parts of Australia's uranium boom is that China is

drooling over the huge Aussie reserves. The land down under is set to

supply the Chinese with 2,500 metric tons of uranium every year to fuel

their nuclear program. But this isn't even a third of the Chinese

demand!

Trust me, as the spot price for uranium approaches the $100 per pound

mark, Australia's mining companies will explode. Uranium's growth has

spurred the government to reconsider its policy of "no new uranium

mines."

But whenever you look at the future of uranium, you'll always end up

in Canada, which holds roughly 15% of global uranium reserves and is the

world's leading producer.

So the opportunity to cash in is still there for the taking, since

some of these tiny companies are virtually unknown. And the truth is

that the vast wealth of natural resources in Canada provides smaller

companies with the chance of tremendous growth.

Until next time,

Keith Kohl

Media / Interview Requests? Click Here.

Uranium Boom and Plutonium Bust: Russia, Japan, China and the World

Peter LeeOver the last decade, the world of fissionable material has experienced a quiet revolution. Plutonium, once the lethal darling of nations seeking a secure source of fuel for their nuclear reactors (and their nuclear weapons) has fallen from favor. Uranium has replaced plutonium as the feedstock of choice for the world’s nuclear haves. And business is booming.

Asian powers like China and India, concerned about energy security and environmental degradation—and despite the disaster at Fukushima—are turning to nuclear power. The demand for uranium is expected to grow by over 40% over the next five years.

The Australian - Global Uranium Demand Expected To Skyrocket

In an unexpected but, in retrospect, logical development, Russia is emerging as the dominant global player in the nuclear fuel industry, with the apparent acquiescence of the United States. Today, as Russia sheds some of its bloated Soviet-era nuclear arsenal, it ships legacy plutonium to the United States to provide almost half of the fuel burned in American nuclear plants. At the same time, the Russian government is moving aggressively to establish its state-run nuclear corporation, ARMZ, as a dominant player in the worldwide rush to increase uranium production.

Russia brings some unique advantages to the nuclear fuel business. The first is an impressive stockpile of excess plutonium. This, however, is a wasting asset as Russia works through its current inventory without generating significant new quantities of metal. Russia is keeping its fingers in the plutonium pot through a program of constructing fast breeder reactors—which generate a surplus of plutonium—despite their technical, safety, and cost headaches.

The second and most crucial advantage is what one might characterize as a determinedly cavalier attitude toward the hazards of nuclear waste, reinforced by the fact that Russia is already a nightmare of nuclear contamination. In fact, it is possible that any additional shipments of nuclear waste to Russia will not contribute significantly to the already dire state of affairs.

Nuclear waste is unpopular, as the successful effort to block the US disposal facility at Yucca Mountain attests. Russia’s ability to absorb it—despite growing anxiety and activism within the country—is a major competitive advantage. Countries and companies that burn nuclear fuel but have no local recourse except on-site storage are naturally interested—and sometimes legally compelled—to source their material from a supplier that is willing to accept and dispose of the waste.

Russia—even though its domestic uranium reserves are rather paltry—has become a major player in uranium production through investments in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and other nations. Mr. Putin and the Russian government has played geopolitical hardball in order to improve the competitive position of its ARMZ Uranium Holding Company, as the Mongolian example discussed below demonstrates.

Russia’s pivot toward uranium can be contrasted instructively with Japan’s. Plutonium can be regarded as one of Japan’s biggest misplaced industrial policy bets. As a very interesting article by Joseph Trento of the investigative organization National Security News Service, reveals, in the 1970s the Japanese government decided that Japan had to have a closed nuclear fuel cycle, in which plutonium would be generated in significant amounts in fast breeder reactors, extracted from spent nuclear fuel, and funneled back into Japanese nuclear power plants.

DC Bureau - United States Circumvented Laws To Help Japan Accumulate Tons Of Plutonium

The ostensible motivation for this policy was the scarcity of the uranium alternative. Nowadays, when uranium reserves are turning up on every continent (and, in the case of Kazakhstan, low-assay ores are processed in situ economically, if not particularly attractively, with a dousing of injected acid and recovered), it is difficult to recall that the dominant perception in the last century was of a uranium shortage.

The Japanese government declared it did not want to substitute uranium import dependence for hydrocarbon dependence, and it wanted to establish its nuclear power industry on the basis of breeder reactors creating plutonium and processing plants separating out the metal for fabrication into fuel—a closed cycle that would render Japan self-sufficient in nuclear material.

It appears that Japan also had two less apparent, or at least less-publicized, motives.

The first was to give Japanese industry—specifically Mitsubishi Heavy Industries—a leg-up in becoming a dominant global force in supplying fast-breeder technology and equipment, a process that was expected to dominate civilian nuclear power generation in the 21st century since it produced more nuclear fuel than it burned.

The second was to generate a reassuring pile of weapons-grade plutonium at a time when the United States was cozying up to a nuclear-capable China as a counterweight to the USSR, and Japan had to confront the possibility that it might be left to find its own security/defense way in the Pacific region.

This effort required US technical assistance. The deal was done with the Reagan administration in a sweetheart arrangement along the lines of what the Bush and Obama administrations gave this century’s anti-Communist counterweight, India. Unlike other nations, Japan could dispose of its plutonium-rich waste at its own discretion.

Japan embarked on a major nuclear energy program and generated sizable quantities of nuclear waste. At the same time, the Japanese government poured billions of dollars into fast breeder and reprocessing projects based on US technology that yielded few tangible results and some genuine nuclear hazard scares, such as the cooling system leak that occurred in at the experimental breeder reactor facility at Monju in 1995 and shut down the facility for 14 years.

Monju |

Jan-Feb 2010 Citizen's Nuclear Information Newsletter

Despite a 2006 government report estimating that the cost of reprocessing spent nuclear fuel over the next 40 years would amount to 18 trillion yen, the Japanese energy establishment appears to be in the grip of political and technological inertia and is still proceeding with its program (although non-proliferation expert Frank von Hippel pointed out that mothballing the Rokkasho plant would still provide ample jobs “for decades” for the adjacent village: decontamination expenses related to the current storage operations alone would amount to 1.5 trillion yen).

Japan's Spent Fuel and Plutonium Management Challenges - Katsuda & Suzuki

Kyodo News// Opinion - "Reconsidering the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant

Without viable local processing capability, Japan stored some of its waste in cooling ponds on site (such as in the cooling ponds now bedeviling Fukushima), at Rokkasho, and at an interim storage facility. The rest is shipped to France and Great Britain, the only two countries that still maintain a reprocessing capability.

Now, despite a stated policy of no surplus plutonium, Japan is the proud owner of an estimated 46 tons of plutonium—ten tons of it in country, the rest of it held by France and Great Britain on its behalf. If Rokkasho operates as planned, Japan’s total plutonium stock would triple by 2020.

For comparison purposes, China is estimated to hold less than 20 tons of highly enriched uranium and a small amount of plutonium. The PRC has probably not produced any weapons-grade fissile material since 1990.

Tehelka - the secret of India's nuke stocks is out

While the world wrings its hands over Iran and its 15 pounds of highly enriched uranium, Japan appears the more pressing nuclear weapon breakout threat.

CNS - civil highly enriched uranium: who has what?

A focus of US diplomacy is keeping the Japanese nuclear weapons dragon bottled up. A weaponized Japan, in addition to generating a certain amount of regional anxiety and triggering an arms race, could turn into an Israel of the Pacific i.e. a titular US ally but with its own security policy more beholden to national interests, fears, and politics than US strategic priorities.

Not unsurprisingly, South Korea, surrounded by actual and potential nuclear weapons states, is trying to go the spent fuel reprocessing route, but has, at least for now been rebuffed by the United States. After the current US-Korea nuclear treaty expires in 2014—and the US will still be unable to offer South Korea any spent fuel storage options—it remains to be seen how firm US resolve will remain.

South Korean Reprocessing: An Unnecessary Threat to the Nonproliferation Regime

Overall, today, the world finds itself in a situation in which plutonium is passé and uranium is de rigeur.

Russia continues to build breeder reactors as part of its nuclear portfolio but has shifted its focus to uranium. China operates a small experimental program. India runs a big unit to generate plutonium for its weapons program. And, there’s Japan. That’s about it.

The US, France, and UK have all shut down their breeder reactors. The UK is considering a shutdown of its Sellafield processing facility because of slackened demand, and is looking at ways to burn weapons-grade nuclear fuel directly into a reactor.

Uranium brings its own matrix of advantages and headaches. Not only is uranium ore relatively plentiful, improvements in centrifuging allow it to be enriched to fuel and weapons grade in a relatively efficient and elegant way compared to the massive diffusion plants that were the norm at Oak Ridge during the 1940s and 1950s.

Perhaps it has become too cheap and easy to pursue the uranium route, as the examples of Pakistan, Libya, Iran, and North Korea imply.

Non-proliferation, instead of relying on the technical and financial barriers erected by the fiendish complexities of generating, separating, and refining plutonium metal or gaseous diffusion of uranium hexafluoride, must turn to the use of sanctions and sabotage (such as the Stuxnet worm) to deter unwelcome actors.

And the general eagerness to advance the commercial development of the nuclear industry has placed Russia—hardly a reliable or benevolent partner of the West—near the center of the world uranium industry with a vested strategic and economic industry in promoting its expansion.

In the case of Iran, a prime customer for Russian nuclear technology and fuel, Moscow is clearly going beyond business imperatives acting in the service of geostrategic calculations that the United States and its allies decidedly do not share.

Meanwhile, Iran’s neighbors such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey pursue nuclear energy agreements with Russian and Chinese support. In the Saudi case, Prince Faisal bluntly stated that the Kingdom is interested in nuclear weapons, not just nuclear power.

Saudi Arabia may seek nuclear weapons prince says.

With the decline of plutonium, the proliferation dangers of nuclear energy have not ended. They have simply mutated in response to the new commercial and technological imperatives of the uranium industry.

Peter Lee writes on East and South Asian affairs and their intersection with US global policy. He is the moving force behind the Asian affairs website China Matters which provides continuing critical updates on China and Asia-Pacific policies. His work frequently appears at Asia Times.

Appendix, Mainichi Shimbun,

Mongolia’s Secret Plan for an International Nuclear Waste Disposal Site

Aikawa HaruyukiThe secret plan surfaced as the crisis at the tsunami-hit Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant has stirred controversy over the pros and cons of nuclear power.

I learned that the Japanese Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry and the U.S. Department of Energy had been secretly negotiating the plan with Mongolia since the autumn of 2010 when I interviewed a U.S. nuclear expert on the phone on April 9, 2011.

"Would you please help the Mongolian people who know nothing about the plan. Mongolia is friendly to Japan, Japanese media certainly has influence on the country," the expert said.

I flew to Ulan Bator, the capital of Mongolia, on April 22, and met with then Ambassador Undraa Agvaanluvsan with the Mongolian Foreign Ministry in charge of negotiations on the plan, at the VIP room of a cafe.

Before I asked the ambassador some questions getting to the heart of the plan, we asked my interpreter to leave the room just as we had agreed in advance. The way the ambassador talked suddenly became more flexible after I stopped the recorder and began asking her questions in English. She explained the process and the aim of the negotiations and even mentioned candidate sites for the disposal facility.

After the interview that lasted for more than two hours, the ambassador said she heard of a similar plan in Australia and asked me to provide Mongolia with any information on it, highlighting the Mongolian government's enthusiasm about overcoming competition with Australia in hosting the disposal facility.

I subsequently visited three areas where the Mongolian government was planning to build nuclear power stations. Japan and the United States were to provide nuclear power technology to Mongolia in return for hosting the disposal facility. I relied on a global positioning system for driving in the vast, grassy land to head to the sites. All the three candidate sites, including a former air force base about 200 kilometers southeast of Ulan Bator, are all dry land. No source of water indispensable for cooling down nuclear reactors, was found at any of these sites and a lake at one of the sites had dried up.

Experts share the view that nuclear plants cannot be built in areas without water. I repeatedly asked Mongolian officials responsible for nuclear power policy how they can build nuclear plants at the sites without water. However, they only emphasized that all the three sites meet the safety standards for nuclear plants set by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

An Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry official, who is familiar with Mongolian affairs, said, "Mongolians are smart but their knowledge of atomic energy isn't that good ..."

In other words, Japan and the United States proposed to build a spent nuclear waste disposal facility in Mongolia, a country that has little knowledge of nuclear energy.

In 2010, the administration of then Prime Minister Kan Naoto released a new growth strategy with special emphasis on exports of nuclear power plants. However, there is no facility in Japan that can accept spent nuclear fuel, putting itself at a disadvantage in its competition with Russia, France and other countries that have offered to sell nuclear plants and accept radioactive waste as a package. A Japanese negotiator said, "The plan to build a disposal facility in Mongolia was aimed at making up for our disadvantage in selling nuclear power stations."

The United States wanted to find another country that will accept spent nuclear fuel that can be converted to materials to develop nuclear weapons in a bid to promote its nuclear non-proliferation policy.

Both the Japanese and U.S. ideas are understandable. However, as Mongolia has just begun developing uranium mines and has not benefited from atomic energy, I felt that it would be unreasonable to shift radioactive waste to Mongolia without explaining the plan to the Mongolian people.

During my stay in Mongolia, I learned that many people there donated money equal to their daily wages to victims of the March 11, 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. I was also present when the Mongolian people invited disaster evacuees from Miyagi Prefecture to their country. I could not help but shed tears when seeing the Mongolian people's goodwill. My interpreter even joked, "You cry too much."

I did not feel a sense of exaltation from learning the details of the secret negotiations on the disposal site. I rather felt ashamed of being a citizen of Japan, which was promoting the plan.

The Fukushima nuclear crisis that broke out following the March 11, 2011 quake and tsunami has sparked debate on overall energy policy. Some call for an immediate halt to nuclear plants while others insist that such power stations are indispensable for Japan's overall energy, industrial and security policies.

"The matter isn't limited to nuclear energy. Our generations have consumed massive amounts of oil and coal," a Finish government official said.

The Mainichi scoop on the secret plan sparked campaigns in Mongolia to demand that the plan on a spent nuclear fuel disposal facility be scrapped and that relevant information be fully disclosed.

Bowing to the opposition, Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj declared in the U.N. General Assembly session in September last year that the country can never host a radioactive waste disposal facility.

Amano Yukiya, director general of the IAEA, which is dubbed a "nuclear watchdog," says, "Those who generate radioactive waste must take responsibility for disposing of it. It's unfair to expect someone else to take care of it."

However, human beings have yet to find a solution to problems involving nuclear waste.

Aikawa Haruyuki, Europe General Bureau, Mainichi Shimbun

(Mainichi Japan) March 13, 2012

Click [here] for the original Japanese story.

Click [here] for the original English : Mainichi scoop on Mongolia's nuclear plans highlights problems in dealing with waste.

Recommended citation: Peter Lee, "Uranium Boom and Plutonium Bust: Russia, Japan, China and the World," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 18, No. 1.

Articles on related subjects

• Peter Hayes, Global Perspectives on Nuclear Safety and Security After 3-11 [here]

• Peter Lee, A New ARMZ Race: The Road to Russian Uranium Monopoly Leads Through Mongolia [here]

• Miles Pomper, Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, Stephanie Lieggi, and Lawrence Scheinman, Nuclear Power and Spent Fuel in East Asia: Balancing Energy, Politics and Nonproliferation [here]

• Richard Tanter, Arabella Imhoff and David Von Hippel, Nuclear Power, Risk Management and Democratic Accountability in Indonesia: Volcanic, regulatory and financial risk in the Muria peninsula nuclear power proposal [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Sino-Russian Alliance Comes of Age: Geopolitics and Energy Politics [here]

• Geoffrey Gunn, Southeast Asia’s Looming Nuclear Power Industry [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Russia, Iran and Eurasian Energy Politics [here]

- See more at: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Peter-Lee/3743#sthash.tDYHK83w.dpuf

Having trouble viewing this issue? Click here.

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/?shva=1#all/1427611bb9be2ddc

Four Gas Stocks You Need to Own

Most investors are completely clueless.

But right now, the largest energy deal in history is quietly unfolding...

A deal that's about to let four tiny gas companies reel in profit margins 1,740% LARGER than anyone else in the

business.

A deal so profitable, we've never seen anything like it before.

A deal that could hand you more money than you know what to do with!

Uranium Boom

By Nick Hodge | Wednesday,

November 20th, 2013

Uranium prices have been on a downward slide for half a decade now.

Trading around $35 per pound, uranium simply can't stay this low for much longer.

Over the coming months and years, uranium prices will creep higher — and uranium companies sitting on

currently undervalued deposits will offer investors tremendous upside.

Let me explain...

Advertisement

You've probably heard about the new banking "policies" that are being put in effect in November and December of

2013 — policies that restrict wire transfers, taking out your OWN money, and more.

The banks are in cahoots with politicians and big companies to screw you over.

Now is the time to take back control over your money. Don't wait till it's too late. To watch the video, click HERE...

The Last Uranium Boom

The last uranium boom kicked off in 2005 as part of the "commodity supercycle."

Its upward ascent ultimately peaked in June 2007 at around $140 pound. Oil would touch $145 a year later.

Commodities were already in an upward trend. But something special happened to uranium...

Commodities were already in an upward trend. But something special happened to uranium...

A new uranium mine called Cigar Lake was supposed to come online in 2007. It is the largest undeveloped high-grade

uranium mine in the world.

However, Cigar Lake didn't come online. Instead, it experienced a major flood.

With the world expecting this new source

of uranium supply, prices started spiking quickly — all the way up to

$138 per pound — before the popping of the housing bubble and the

financial crash brought them back down. The incident at Fukushima helped

keep

them low.

Now things are starting to change...

Uranium demand is starting to creep back up. And with Cigar Lake still in a perpetual state of limbo, the world is

starting to scramble for new supply.

The stage is set for a new uranium boom.

Advertisement

34 Billion Barrels of Oil Up for Grabs in New Zealand

I've found two tiny companies in the Kiwi nation that control over 5,000 square miles of land so rich with oil, it's

literally leaking to the surface...

Estimates show they could be sitting on over 34 billion barrels of oil. That's billion with a 'b'.

If you missed out on getting in early on the shale rush in the United States, this could be your last best chance to

bank massive gains. Here's how to grab your

share.

Why Uranium, Why Now?

At the very basic level, there simply isn't enough supply to meet demand. The world's reactors will need 65,000

tonnes of uranium in 2013; but the world's mines will only produce around 58,000 tonnes.

Some of the difference is made up with reprocessed fuel, but a supply crunch still looms for a litany of reasons.

For starters, global electricity demand is growing twice as fast as overall energy demand. Worldwide demand for

electricity will rise 75% by 2035.

Nuclear is the cleanest (no emissions) and safest (per kWh generated) than any other fuel source. It will be the

go-to source for the world to provide clean baseload energy.

Even Japan is not shying away, with Prime Minister Abe calling those who want to end nuclear power in Japan

"irresponsible."

There are nearly 70 reactors under construction worldwide, more than 160 planned, and 315 proposed...

According to Rockstone Research:

A supply shortage is

anticipated post-2013/2014: primary supply capacity must increase by

around

90 million lbs. U3O8 in the next 6 years until 2020 only to meet demand

requirements. During the last 8 years (2003-2011), global mine output

solely

increased by 48 million lbs...

For output to increase to meet rising future demand, uranium prices have to rise. That's why analyst forecasts for

uranium prices in 2014 and 2015 are some 65% to 85% higher than they are today.

Lastly, some 20 million pounds of uranium per year have been coming to the United States from Russia for the past 20

years. For reasons I lay out here, this

agreement will soon come to an abrupt end, leaving a wide gap in U.S. uranium supply.

With uranium prices slated to rise some 85% in the coming two years, what's the best way to play it?

Uranium Investing in 2014 and Beyond

Because uranium stocks typically rise 2x-4x the rate of the underlying uranium price, my money is on uranium

stocks.

There's a reason uranium miners like Cameco (NYSE: CCJ), Denison (AMEX: DNN), and Areva (PA: AREVA) are outperforming

the market twice over (or more) since mid-October:

Advertisement

Silver is Going to $100

Legendary asset manager Eric Sprott said this will be "the decade of silver," during which silver will hit $100.

While you could certainly do well owning the physical metal itself, there's an even better way you could take

advantage of it — for less than $1.

This is only a sign of things to come.

Increasingly, one region is being looked to as a large supplier of future uranium. Currently, the Athabasca Basin

provides 16% of global uranium production. This is second only to Kazakhstan.

Over the next few years, though, Athabasca will be the fastest-growing area for uranium production in the word. Its

output is expected to double by 2020.

This is and will continue to happen for many reasons:

- Canada is the world's friendliest mining country;

- Athabasca is utterly underexplored, with only the eastern portion in production;

- The mines there are young and growing, and will easily outpace growth in Kazakhstan; and

- The deposits are generally the shallowest and most high-grade in the world (10 of the 15 highest-grade deposits are in Athabasca)

For these reasons (and more, which I outline here), Athabasca is about to become the world's uranium hotspot.

There's already a land rush on...

A bidding war between Cameco and Rio

Tinto (NYSE: RIO) for Hathor's Roughrider deposit ended at $642 million

in early

2012. Denison paid $71 million to Fission Energy for a portfolio of

projects in the area earlier this year. It's also made a $26 million

offer to take

out Rockgate Capital (TSX: RGT). Areva owns 37% of Cigar Lake, 30% of

McArthur River, and the majority of the Midwest Mine.

But it's still extremely early...

This uranium grab is only getting started. The western and northern portions of the basin are only now being

explored, and they look very impressive.

The tiny exploration companies that own them will grow by giant multiples as uranium price start their climb toward

$70 per pound.

I have my eye on two of them specifically — and I went to visit them a few weeks ago, more than 2,500

miles from Baltimore.

So you can get ahead of the crowd on this one, I've put together a video detailing all the reasons for the coming

uranium rush, my tour of the western Athabasca Basin, and why these

two companies are poised for the highest gains.

Call it like you see it,

Nick Hodge

Nick is the Founder and President of the Outsider Club, and

the Investment Director of the

thousands-strong stock advisory, Early Advantage. Co-author of two

best-selling investment books, including Energy Investing for Dummies,

his insights

have been shared on news programs and in magazines and newspapers

around the world. For more on Nick, take a look at his editor's page.

Uranium Boom and Plutonium Bust: Russia, Japan, China and the World

Peter LeeOver the last decade, the world of fissionable material has experienced a quiet revolution. Plutonium, once the lethal darling of nations seeking a secure source of fuel for their nuclear reactors (and their nuclear weapons) has fallen from favor. Uranium has replaced plutonium as the feedstock of choice for the world’s nuclear haves. And business is booming.

Asian powers like China and India, concerned about energy security and environmental degradation—and despite the disaster at Fukushima—are turning to nuclear power. The demand for uranium is expected to grow by over 40% over the next five years.

The Australian - Global Uranium Demand Expected To Skyrocket

In an unexpected but, in retrospect, logical development, Russia is emerging as the dominant global player in the nuclear fuel industry, with the apparent acquiescence of the United States. Today, as Russia sheds some of its bloated Soviet-era nuclear arsenal, it ships legacy plutonium to the United States to provide almost half of the fuel burned in American nuclear plants. At the same time, the Russian government is moving aggressively to establish its state-run nuclear corporation, ARMZ, as a dominant player in the worldwide rush to increase uranium production.

Russia brings some unique advantages to the nuclear fuel business. The first is an impressive stockpile of excess plutonium. This, however, is a wasting asset as Russia works through its current inventory without generating significant new quantities of metal. Russia is keeping its fingers in the plutonium pot through a program of constructing fast breeder reactors—which generate a surplus of plutonium—despite their technical, safety, and cost headaches.

The second and most crucial advantage is what one might characterize as a determinedly cavalier attitude toward the hazards of nuclear waste, reinforced by the fact that Russia is already a nightmare of nuclear contamination. In fact, it is possible that any additional shipments of nuclear waste to Russia will not contribute significantly to the already dire state of affairs.

Nuclear waste is unpopular, as the successful effort to block the US disposal facility at Yucca Mountain attests. Russia’s ability to absorb it—despite growing anxiety and activism within the country—is a major competitive advantage. Countries and companies that burn nuclear fuel but have no local recourse except on-site storage are naturally interested—and sometimes legally compelled—to source their material from a supplier that is willing to accept and dispose of the waste.

Russia—even though its domestic uranium reserves are rather paltry—has become a major player in uranium production through investments in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and other nations. Mr. Putin and the Russian government has played geopolitical hardball in order to improve the competitive position of its ARMZ Uranium Holding Company, as the Mongolian example discussed below demonstrates.

Russia’s pivot toward uranium can be contrasted instructively with Japan’s. Plutonium can be regarded as one of Japan’s biggest misplaced industrial policy bets. As a very interesting article by Joseph Trento of the investigative organization National Security News Service, reveals, in the 1970s the Japanese government decided that Japan had to have a closed nuclear fuel cycle, in which plutonium would be generated in significant amounts in fast breeder reactors, extracted from spent nuclear fuel, and funneled back into Japanese nuclear power plants.

DC Bureau - United States Circumvented Laws To Help Japan Accumulate Tons Of Plutonium

The ostensible motivation for this policy was the scarcity of the uranium alternative. Nowadays, when uranium reserves are turning up on every continent (and, in the case of Kazakhstan, low-assay ores are processed in situ economically, if not particularly attractively, with a dousing of injected acid and recovered), it is difficult to recall that the dominant perception in the last century was of a uranium shortage.

The Japanese government declared it did not want to substitute uranium import dependence for hydrocarbon dependence, and it wanted to establish its nuclear power industry on the basis of breeder reactors creating plutonium and processing plants separating out the metal for fabrication into fuel—a closed cycle that would render Japan self-sufficient in nuclear material.

It appears that Japan also had two less apparent, or at least less-publicized, motives.

The first was to give Japanese industry—specifically Mitsubishi Heavy Industries—a leg-up in becoming a dominant global force in supplying fast-breeder technology and equipment, a process that was expected to dominate civilian nuclear power generation in the 21st century since it produced more nuclear fuel than it burned.

The second was to generate a reassuring pile of weapons-grade plutonium at a time when the United States was cozying up to a nuclear-capable China as a counterweight to the USSR, and Japan had to confront the possibility that it might be left to find its own security/defense way in the Pacific region.

This effort required US technical assistance. The deal was done with the Reagan administration in a sweetheart arrangement along the lines of what the Bush and Obama administrations gave this century’s anti-Communist counterweight, India. Unlike other nations, Japan could dispose of its plutonium-rich waste at its own discretion.

Japan embarked on a major nuclear energy program and generated sizable quantities of nuclear waste. At the same time, the Japanese government poured billions of dollars into fast breeder and reprocessing projects based on US technology that yielded few tangible results and some genuine nuclear hazard scares, such as the cooling system leak that occurred in at the experimental breeder reactor facility at Monju in 1995 and shut down the facility for 14 years.

Monju |

Jan-Feb 2010 Citizen's Nuclear Information Newsletter

Despite a 2006 government report estimating that the cost of reprocessing spent nuclear fuel over the next 40 years would amount to 18 trillion yen, the Japanese energy establishment appears to be in the grip of political and technological inertia and is still proceeding with its program (although non-proliferation expert Frank von Hippel pointed out that mothballing the Rokkasho plant would still provide ample jobs “for decades” for the adjacent village: decontamination expenses related to the current storage operations alone would amount to 1.5 trillion yen).

Japan's Spent Fuel and Plutonium Management Challenges - Katsuda & Suzuki

Kyodo News// Opinion - "Reconsidering the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant

Without viable local processing capability, Japan stored some of its waste in cooling ponds on site (such as in the cooling ponds now bedeviling Fukushima), at Rokkasho, and at an interim storage facility. The rest is shipped to France and Great Britain, the only two countries that still maintain a reprocessing capability.

Now, despite a stated policy of no surplus plutonium, Japan is the proud owner of an estimated 46 tons of plutonium—ten tons of it in country, the rest of it held by France and Great Britain on its behalf. If Rokkasho operates as planned, Japan’s total plutonium stock would triple by 2020.

For comparison purposes, China is estimated to hold less than 20 tons of highly enriched uranium and a small amount of plutonium. The PRC has probably not produced any weapons-grade fissile material since 1990.

Tehelka - the secret of India's nuke stocks is out

While the world wrings its hands over Iran and its 15 pounds of highly enriched uranium, Japan appears the more pressing nuclear weapon breakout threat.

CNS - civil highly enriched uranium: who has what?