Perang Rahasia Soeharto

https://intranet2012.wordpress.com/2012/11/29/perang-rahasia-soeharto/

Setelah membahas peranan sipil menghadang pengaruh Aidit cs di https://intranet2012.wordpress.com/2012/10/29/3-menguak-aidit/ maka sekarang akan dibahas peranan pihak intel-militer cq jendral Suharto menghadang polit biro

Kalau melihat karir jendral Suharto maka tampaklah bahwa setiap orang mempunyai kelebihan dan kekurangan dan tentu saja sudah lumrah bahwa selalu ada yang setuju dan ada yang tidak setuju dengan sepak terbangnya

Ucapannya (“Criminal matters became a secondary problem,” , “what was most important were matters of a political kind”) menjadi dasar untuk menhalalkan korupsi, penyelundupan, kronisme demi politik praktis

Sebagai orang dibawah naungan Gemini maka

Positip : Tetap menghormati seniornya AH.Nasution dengan juga memberi gelar “jendral besar” Negatip : Menggeser AH.Nasution dari jabatan ketua MPRS

Positip : Memberi bintang jasa pada paman saya Said Reksohadiprodjo untuk bidang pendidikan Negatip : Sebelumnya menggeser paman saya demi kepentingan sesama militer

Perihal SEATO

Baik jendral AH.Nasution, A.Yani dan Suharto karirnya lagi berkibar tidak lama setelah SEATO dibentuk pada tanggal 8 September 1954 di Manila sesuai dengan doktrin the American Truman Doctrine of creating anti-communist bilateral and collective defense treaties

Anggautanya merupakan kombinasi negara barat yang anti komunis, Inggris, Perancis, Amerika , New Zealand, Pakistan, Pilipina, Thailand

Pakistan keluar di tahun 1972 setelah kemerdekaan Bangladesh, Perancis membatalakan bantuan keuangan di tahun 1975,on 20 February 1976

SEATO bubar pada tanggal 30 June 1977.

Walaupun SEATO bubar maka sekarang kegiatannya diganti oleh CIA dengan bantuan ekonomi/pelatihan ke agen agen di negara negara Asia Tenggara

Sejarah CIA – Seskoad

Sejak 1953, AS berkepentingan untuk membantu mencetuskan krisis di Indonesia, yang diakui sebagai “penyebab langsung” yang merangsang BK mengakhiri sistem parlementer Indonesia dan menyatakan berlakunya keadaan darurat militer, serta memasukkan “korp perwira” secara resmi dalam kehidupan politik (14 Maret 1957) Sedangkan langkah-langkah yang dilakukan CIA untuk mewujudkan ambisinya tersebut yakni dengan menggandeng faksi militer kanan –seperti Soeharto, Walandouw, Suwarto, Sarwo Edhie, Kemal Idris, Ibnu Sutowo, Basuki Rahmat, Djuhartono

Kontrol terhadap AD ini dianggap penting, karena AS menganggap hanya AD yang mampu mengimbangi kekuatan PKI. Lalu didirikanlah SESKOAD tahun 1958 di Bandung yang mendapatkan dukungan penuh dari Pentagon, RAND dan Ford Foundation

Khusus bagi jenderal Suharto dunia inteligen bukan hal yang baru baginya karena di tahun 1959 gara gara skandal penyelundupan dimutasikan ke Seskoad di Bandung dan pula sejak berpangkat brigadier-general di tahun 1960, telah diangkat menjadi kepala inteligen Angkatan Darat … jangan jangan sebelumnya sudah ada ikatan kerjasama dengan CIA ..

Ketika Kolonel Suharto menjabat sebagai Panglima Diponegoro, ia dikenal sebagai sponsor penyelundupan dan berbagai tindak pelanggaran ekonomi lain dengan dalih untuk kesejahteraan anak buahnya. Suharto membentuk geng dengan sejumlah pengusaha seperti Lim Siu Liong, Bob Hasan, dan Tek Kiong, konon masih saudara tirinya. Dalam hubungan ini Kolonel Suharto dibantu oleh Letkol Munadi, Mayor Yoga Sugomo, dan Mayor Sujono Humardani. Komplotan bisnis ini telah bertindak jauh antara lain dengan menjual 200 truk AD selundupan kepada Tek Kiong.

Persoalannya dilaporkan kepada Letkol Pranoto Reksosamudro yang ketika itu menjabat sebagai Kepala Staf Diponegoro, bawahan Suharto. Maka MBAD membentuk suatu tim pemeriksa yang diketuai Mayjen Suprapto dengan anggota S Parman, MT Haryono, dan Sutoyo. Langkah ini diikuti oleh surat perintah Jenderal Nasution kepada Jaksa Agung Sutarjo dalam rangka pemberantasan korupsi untuk menjemput Kolonel Suharto agar dibawa ke Jakarta pada 1959. Ia akhirnya dicopot sebagai Panglima Diponegoto dan digantikan oleh Pranoto. Kasus Suharto tersebut akhirnya dibekukan karena kebesaran hati Presiden Sukarno (D&R, 3 Oktober 1998:18).

Nasution mengusulkan agar Suharto diseret ke pengadilan militer, tetapi tidak disetujui oleh Mayjen Gatot Subroto … Kemudian ia dikirim ke Seskoad di Bandung

Selanjutnya ketika Suharto hendak ditunjuk sebagai Ketua Senat Seskoad, hal itu ditentang keras oleh Brigjen Panjaitan dengan alasan moralitas

Di Bandung Kolonel Suharto bertemu dengan Kolonel Suwarto, Wadan Seskoad, hal ini sangat berpengaruh terhadap perjalanan hidup Suharto selanjutnya. Sekolah Komando Angkatan Darat (Seskoad) di Bandung yang telah berdiri sejak 1951 ini merupakan sebuah think tank AD, pendidikan militer Indonesia tertua, terbesar dan paling berpengaruh. Seskoad telah menjadi tempat penggodogan perkembangan doktrin militer di Indonesia. Sampai 1989 telah meluluskan 3500 perwira. Para alumninya menjadi tokoh terkemuka dalam pemerintahan. Hampir 100 orang menjadi sekretaris jenderal, gubernur, pimpinan lembaga-lembaga nasional atau badan-badan non departemental. Presiden, Wakil Presiden, dan lebih 30 menteri merupakan alumni Seskoad.

Suwarto sendiri pernah menempuh pendidikan Infantry Advance Course di Fort Benning pada 1954 dan Command and General Staff College di Fort Leavenworth, AS pada 1958. Ia bersahabat dengan Prof Guy Pauker, konsultan RAND (Research and Development Corporation) yang dikunjunginya pada 1963 dan 1966. Suwartolah yang menjadikan Seskoad sebagai think tank politik MBAD, mengarahkan para perwira AD menjadi pemimpin politik potensial (Sundhaussen 1988:245).Guy Pauker adalah pengamat masalah Asia, orang penting dalam Rand Corporation, kelompok pemikir (think tank) CIA*. Sejak itu Seskoad biasa disebut sebagai negara dalam negara, membuat garis politiknya sendiri, bahkan mempunyai perjanjian kerjasama dan bantuan dari AS terlepas dari politik pemerintah RI.

Suharto, murid baru yang masuk pada Oktober 1959 ini telah mendapatkan perhatian besar dari sang guru. Pada awal 1960-an Suharto dilibatkan dalam penyusunan Doktrin Perang Wilayah serta dalam kebijaksanaan AD dalam segala segi kegiatan pemerintah dan tugas kepemerintahan. Peran Suharto dalam civic mission menempatkan dirinya dan sejumlah opsir yang condong pada PSI dalam pusat pendidikan dan pelatihan yang disokong oleh CIA lewat pemerintah AS, suatu program bersifat politik (Scott 1999:81). Pada masa Bandung Kolonel Suharto inilah agaknya hubungan Suwarto-Syam-Suharto-CIA mendapatkan dimensi baru

Seskoad memancarkan pamornya sebagian besar karena jasa Suwarto, sangat besar perannya dalam perkembangan politik. Karena jasanya pula maka Seskoad menjadi pusat pemikiran politik serta menghadapi perkembangan PKI

Perkembangan sejarah menunjukkan bahwa Suharto benar-benar tidak “sebodoh” yang diperkirakan Jenderal Nasution, juga tidak sekedar koppig seperti yang disebut oleh Bung Karno.

Kebetulan atau Balas Dendam

Nama-nama pahlawan revolusi berhubungan langsung dengan peradilan perihal pemecatannya sebagai Panglima Diponegoro karena bertindak sebagai sponsor penyelundupan (team peradilan MBAD – blokir karir)

Ahmad Yani, Jend. Anumerta

Donald Ifak Panjaitan, Mayjen. Anumerta

M.T. Haryono, Letjen. Anumerta

Siswono Parman, Letjen. Anumerta

Suprapto, Letjen. Anumerta

Sutoyo Siswomiharjo, Mayjen. Anumert

Bahan pemikiran

(BENARKAH ISSUE INI..??.. ATW HANYA PEMIKIRAN INTELIGEN.. UTK MEMBUAT SKENARIO.. N SUATU DALIH AGAR ADANYA GERAKAN YG SDH LAMA DI AGENDAKAN..??>> NOTE...??>> SIAPA YG PUNYA AGENDA..?? YG SCR KELENGKAPAN INFO N PUSAT2 KOMUNIKASI AKSI.. NAMPAKNYA BERPUSAT HNY LINK-PK HARTO.. N SYAM.. N AIDIT..??.. SIAPA LAGI SEBENRANYA YNG MENGOLAH INFO INTELIGEN N YG TERLIBAT SCR IN ACTION...?? DIMANA POSISI INTEL SENIOR PK HARTO ...AL: ... YOGA SUGAMA.. N SUTOPO YUWONO..CS ?? N YANG LAENNYA SBG ORG KEPERCAYAAN PK HARTO.. DLM KENDALI MASA.. N MEDIA MASA.. >> KONON ADA ALI MURTOPO N SUDOMO CS..YG BARU KMD MUNCUL SBG POSISI KUNCI KENDALI MASA N LINTAS MILITER ....?? DARI KESIAGAAN N JARINGAN YG DMK LENGKAP.. N TERKONSOLIDASI SCR RAPI N PENUH RAHASIA..?? MK CENTRAL KOMANDO ADA PADA TITIK KOMANDO AGENDA YG LBH FOKUS.. N ORANG2 LAPANGAN YG TERLIBAT AKSI ADALAH KENALAN N DALAM KENDALI KOMADO AKSI MILITER YG SANGAT TERJALIN RAPIH ITU.. HNY PD TITIK ... PK HARTO-SYAM-AIDIT..??>> SDG SAS 1 YANI N NASUTION CS.. SAS 2 SUKARNO.. N SAS 3.. AIDIT..CS.. N PR PELAKU AKSI.. UNTK MMBUNGKAM INFO N DATA2 VALID.. SHINGGA SMW BS DIAMANKAN DLM KENDALI MASA N POLITIK N MILITER..>> SMW PERLU DATA BARU.. N PERLU DIUNGKAP DG BENAR..??>> )

Di Halim bung Sukarno menepuk Supardjo dan berucap “jangan ada pembunuhan lagi”

Pembantu Letnan Dua Djahurub – Prajurit Resimen Tjakrabirwa –

Beragabung dengan pasukan LETTU Doel Arif dan menyerang dan membunuh

Jendral A.H. Nasution (lolos)

Sersan Satu Marinir Hadiwinarto P. Soeradi (NRP. 37265) – Prajurit Resimen Tjakrabirwa

Sersan Satu Marinir Hadiwinarto P. Soeradi (NRP. 37265) – Prajurit Resimen Tjakrabirwa

Sebagai seorang “didikan Syam (PKI)” dengan sendirinya Untung menggangap jendral Nasution cs sebagai jendral berhaluan kanan yang perlu diamankan di area AURI yang dianggap setia pada Soekarno atas arahan Aidit dan Syam

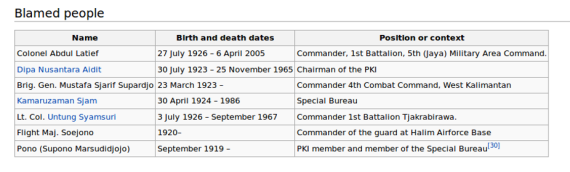

Perihal Pak Harto tidak memberi reaksi atas info dari Kol Latif apakah karena mengetahui bahwa Dewan Jendral itu hanya issue saja dan baru kemudian bereaksi ketika Untung mengumumkan G30S liwat RRI?

CIA saja kecolongan gara gara musuh dalam selimut yang meneruskan kepada PK Cina dan PKI dan percaya atas issue Dewan jendral

Bagaimanakah scenario sebenarnya dari G30S itu ..?

(asumsi..atw bocoran inteligen pk harto..??)

Besar kemungkinan seperti berikut ini:Bung Karno – Untung

Kesalahan fatal menilai sebuah Kesempatan

Syam melihat kesempatan untuk membunuh para jendral dan melimpahkan kesalahan pada masalah intern militer..dewan jendralUntung melihat kesempatan untuk menjadi pimpinan G30S .. berjasa pada bung Karno dan PKI..

Anggota-Anggota Resimen Tjakrabirawa

Komandan Resimen Cakrabirawa , Brigjen Sabur

Brigadir Jendral TNI. Sabur – Komandan Resimen Tjakrabirawa

Kolonel Maulwi Saelan – Wakil Komandan Resimen Tjakrabirawa

Letnan Kolonel Untung bin Syamsuri – Komandan Batalyon I Tjakrabirawa – Pembrontak/Pemimpin PKI

Letnan Kolonel Ali Ebram – Staf Asisten I Intelijen Resimen Tjakrabirawa

Letnan Satu Doel Arif – Komandan Resimen Tjakrabirawa – Pemberontak/Pemimpin Pasukan PKI yang membunuh Jendral-Jendral TNI-AD (Pasukan Pasopati PKI)

Bung Karno – Soepardjo

Keberadaan Brig,Jen Soepardjo (loyal kepada bung Karno) di Jakarta

menjadi teka teki karena seharusnya berada di Kalimantan ..menurut saya

keberadaannya hanya dimungkinkan karena mendapat perintah langsung dari

Bung Karno walaupun merupakan bawahan Soeharto … kenapa dipanggil ke

Jakarta… apakah dalam rangka mengamankan ke-6 jendral yang dianggap

mbalelo…?

Bung Karno – Soeharto

Sebagai seorang yang loyal kepada bung Karno maka besar kemungkinan

Soeharto mengirimkan pasukan Diponegoro dan Brawijaya ke Jakarta untuk

ber jaga jaga apabila pasukan Siliwangi (Nasution dan Yani) melancarkan

kudeta sesuai isue dewan jendral atau pihak PKI membuat keonaran

Pada waktu itu Brig.jen Soeharto berada diluar lingkaran para jendral … Jen.Nasution pernah mau memecatnya di masa lalu ..Jen.Yani meliwatinya dalam karir..

Kesalahan fatal menilai sebuah Kesempatan

Surat Perintah 11 Maret …merupakan alat untuk menggeser AIDIT sebagai ketua umum PKI liwat Soeharto dan sebagai ketua umum defakto PKI dapat menggendalikan PKI sehingga merasa tidak ada gunanya membubarkan PKI serta juga sebagai pengimbang Junta MiliterBung Karno – CIA

Tentu pihak CIA risih kalau Bung Karno menjadi tokoh Komunis diluar Rusia dan Cina …melihat kesempatan untuk menggesernya dengan keberadaan SP 11 Maret tersebutBaca pula https://intranet2012.wordpress.com/2012/10/29/3-menguak-aidit/

Sepintas lalu kelihatan bahwa hubungan antara Seskoad dan Polit Biro serasi sekali

Tetapi sesungguhnya ke-2 pihak intel sedang melakukan infiltrasi ke pihak lawan masing masing dan ber-pura pura kompak demi konsep Nasakom

Perihal G30S

Puncak dari pertarungan politik di Indonesia, khususnya pada 1959-1965, adalah Peristiwa 30 September 1965, ketika mereka yang bertarung terjebak kepada pilihan ‘mendahului atau didahului’. Mereka yang mendahului ternyata terperosok, sebagaimana yang didahului pun roboh, dan Soekarno terlindas di tengah persilangan karena gagal meneruskan permainan keseimbangan kekuasaan.

Soekarno, misalnya, dari dirinyalah muncul cetusan untuk menindak para jenderal yang tidak loyal, yang dilaporkan pada dirinya dalam pola intrik istana. Cetusannya itu, terutama kepada Letnan Kolonel Untung, menjadi awal kematian enam jenderal dan seorang perwira menengah, meskipun ia mungkin tidak ‘mengharapkan’ pembunuhan terjadi. Dipa Nusantara Aidit, adalah orang yang mengantar terjadinya peristiwa menjadi kekerasan berdarah ketika ia memanfaatkan Untung yang mendapat perintah penindakan dari Soekarno, dan mendorongkan peristiwa itu terjadi sebagai masalah internal Angkatan Darat, sambil menjalankan rencana jangka panjangnya sendiri. Dan pengelolaan atas masalah internal Angkatan Darat ini, mendapat bentuk yang nyaris ‘sempurna’ sebagai makar dalam penanganan Sjam tokoh Biro Khusus PKI, dengan mengoptimalkan peranan Letnan Kolonel Untung.

Lalu

Jenderal Soeharto muncul dari balik tabir blessing in disguise,

mengambil peran penting dengan segala teka-teki yang untuk sebagian

belum terpecahkan hingga kini. Dan akhirnya, berkuasa

Kenyataan lain yang tidak bisa diabaikan, adalah fakta bahwa Soeharto

lah yang telah membantu dengan radiogramnya mendatangkan dua batalion

dari Jawa Timur dan Jawa Tengah yang terlibat dalam Gerakan 30

September. Soeharto membiarkan dan menunggu sampai ‘bisul’ pecah. Lalu

bertindak. Ini secara kuat mengesankan betapa Soeharto telah bekerja

dengan suatu peran yang abu-abu.

Di pihak militer, adalah Letnan Jenderal Ahmad Yani dan rekan-rekannya para jenderal yang memperoleh ‘peran’ sebagai korban, sesuatu yang sebenarnya bisa ‘dihindarkan’ dengan ketajaman analisa terhadap laporan-laporan intelijen dan gambaran situasi yang ada. Mayor Jenderal Soeharto adalah ‘pihak ketiga’ dalam pergulatan kekuasaan dan untuk sebagian muncul sebagai ‘kuda hitam’ yang tak terduga

Di pihak militer, adalah Letnan Jenderal Ahmad Yani dan rekan-rekannya para jenderal yang memperoleh ‘peran’ sebagai korban, sesuatu yang sebenarnya bisa ‘dihindarkan’ dengan ketajaman analisa terhadap laporan-laporan intelijen dan gambaran situasi yang ada. Mayor Jenderal Soeharto adalah ‘pihak ketiga’ dalam pergulatan kekuasaan dan untuk sebagian muncul sebagai ‘kuda hitam’ yang tak terduga

Ternyata, ia adalah ‘orang lain’ bagi Letnan Jenderal Ahmad Yani dan

kawan-kawan, serta bagi Jenderal Abdul Harris Nasution. Pada sisi dan

episode lain, Soeharto secara kontroversial memerintahkan Kolonel Yasir

Hadibroto untuk langsung ‘mengeksekusi’ mati DN Aidit setelah ia ini

tertangkap di Jawa Tengah.

Dalam menghadapi makar terhadap pemerintah, menurut standar normal,

tertangkapnya tokoh yang dianggap perencana atau pemimpin makar, justru

merupakan pintu masuk untuk mengungkap segala latar belakang peristiwa.

Untuk mengetahui jaringan makar, sehingga memudahkan untuk menangkap

mereka yang terlibat, untuk selanjutnya diselesaikan melalui jalur

hukum. Bila Soeharto meyakini PKI sebagai partai yang berdiri di

belakang makar, seperti yang sering dikatakannya sendiri di kemudian

hari, semestinya ia ‘menjaga’ Aidit untuk kepentingan interogasi lanjut,

bukannya ‘memerintahkan’ Aidit dieliminasi. Pembunuhan langsung

terhadap Aidit, tidak bisa tidak berarti Soeharto ingin menutupi suatu

rahasia yang bisa terungkap bila Aidit dibiarkan hidup, apapun rahasia

itu.Menurut kabar tokoh tokoh G30S merupakan kenalan lamanya …?

Letkol Untung

Brigjen Soepardjo

Ia berasal dari Divisi Siliwangi, pasukan Suparjo lah yang telah

berhasil menangkap gembong DI Kartosuwiryo dan mengakhiri pemberontakan

DI di Jawa Barat. Kemudian ia ditugaskan ke Kostrad, lalu menjabat

sebagai Panglima Kopur II Kostrad di bawah Jenderal Suharto. Tokoh ini

juga cukup dekat dengan Suharto. Hampir dapat dipastikan bahwa tokoh ini

pun, seperti kedua tokoh sebelumnya yakni Letkol Untung dan Kolonel

Latief, seseorang yang memiliki kesetiaan tinggi kepada Presiden

Sukarno.

Suparjo merupakan anggota kelompok yang biasa disebut kelompok Kolonel Suwarto (Seskoad Bandung), yang di dalamnya terdapat Alamsyah, Amir Makhmud, Basuki Rakhmad, Andi Yusuf, Yan Walandow. Yang terakhir ini seorang kolonel yang ikut pemberontakan Permesta, kemudian menjadi pengusaha. Ia mempunyai hubungan lama dengan CIA dan menjadi petugas Suharto dalam mencari dana dari luar negeri. Ia pun anggota trio Suharto-Syam-Latief cs

Suparjo merupakan anggota kelompok yang biasa disebut kelompok Kolonel Suwarto (Seskoad Bandung), yang di dalamnya terdapat Alamsyah, Amir Makhmud, Basuki Rakhmad, Andi Yusuf, Yan Walandow. Yang terakhir ini seorang kolonel yang ikut pemberontakan Permesta, kemudian menjadi pengusaha. Ia mempunyai hubungan lama dengan CIA dan menjadi petugas Suharto dalam mencari dana dari luar negeri. Ia pun anggota trio Suharto-Syam-Latief cs

Kol.A.Latief

Latief sendiri menyatakan karier kemiliterannya nyaris selalu mengikuti jejak Suharto. Pada gilirannya membuat hubungan Latief dan Suharto bukan lagi sekedar bawahan dan atasan, melainkan sudah sebagai dua sahabat. Suharto tahu Latief tak akan melakukan sesuatu yang dapat merugikan dirinya. Sudah sejak setelah agresi kedua, Latief merasa selalu mendapatkan kepercayaan dari Suharto sebagai komandannya yakni memimpin pasukan pada saat yang sulit. Ketika Trikora pun ia masih dicari bekas komandannya itu, tetapi Latief sedang mengikuti Seskoad. Pada bulan Juni 1965 Mayjen Suharto meminta agar Latief dapat memimpin suatu pasukan di Kalimantan Timur, akan tetapi Umar Wirahadikusuma menolak melepasnya karena tenaganya diperlukan untuk tugas keamanan di Kodam V Jaya.

Latief sendiri menyatakan karier kemiliterannya nyaris selalu mengikuti jejak Suharto. Pada gilirannya membuat hubungan Latief dan Suharto bukan lagi sekedar bawahan dan atasan, melainkan sudah sebagai dua sahabat. Suharto tahu Latief tak akan melakukan sesuatu yang dapat merugikan dirinya. Sudah sejak setelah agresi kedua, Latief merasa selalu mendapatkan kepercayaan dari Suharto sebagai komandannya yakni memimpin pasukan pada saat yang sulit. Ketika Trikora pun ia masih dicari bekas komandannya itu, tetapi Latief sedang mengikuti Seskoad. Pada bulan Juni 1965 Mayjen Suharto meminta agar Latief dapat memimpin suatu pasukan di Kalimantan Timur, akan tetapi Umar Wirahadikusuma menolak melepasnya karena tenaganya diperlukan untuk tugas keamanan di Kodam V Jaya.

Kenyataan bahwa Latief tidak dihukum mati, menimbulkan suatu spekulasi bahwa ia memiliki keterangan yang lebih sempurna yang disimpan di luar Indonesia dengan pesan supaya segera diumumkan jika ia dibunuh

Kamaruzaman Syam

Pada tahun 1964, ditunjuk sebagai kepala Polit-biro PKI yang terdiri dari 5 orang yaitu:Sjam, Pono (Supono Marsudidjojo), Bono, Wandi dan Hamim.

Ke-3 orang pertama mempunyai tugas berhubungan dengan pihak militer untuk mendapatkan informasi

Semua anggauta diwajibkan untuk menyembunyikan keanggautaan partai di PKI

Setiap bulan mereka bertemu dan meneruskan kepada Aidit untuk mendapatkan perintah selanjutnya .. Hanya Aidit dan beberapa anggauta senior mengetahui keberadaan Polit Biro ini … bagi orang luar maka Sjam-Pono-Bono dikira mata mata militer .. ke-3nya mempunyai kartu identitas untuk masuk ke “Army bases” dan setiap orang mempunyai kontak … tujuan utamanya bukan untuk merekut akan tetapi mendapatkan info dan sebagai gantinya mereka memberikan info perihal teroris muslim …bukankah mereka anti komunis?

Rupanya baik

bung Karno dan Suharto

sudah jauh hari memikirkan cara

bagaimana menjinakan PKI

bung Karno dan Suharto

sudah jauh hari memikirkan cara

bagaimana menjinakan PKI

Kenapa Bung Karno makin dekat ke PKI

Usaha menggambil alih kedudukan Ketua Umum PKI liwat Nasakom dan Pancasila

Usaha menggambil alih kedudukan Ketua Umum PKI liwat Nasakom dan Pancasila

Sebagai seorang sipil Demokrat (semua partai punya hak yang sama) maka jalan yang ditempuh bung Karno adalah melalui konsep Nasakom dan Pancasila untuk menghadang PKI kalu perlu melakukan kudeta ketua umum PKI

Kenapa badan inteligen Militer mendekati Polit Biro ??

Sebagai seorang militer maka Suharto melalui "badan inteligen" melakukan langkah langkah serangan terselubung yang mematikan

Tiada Pilihan selain memainkan lakon Anta Seno gugur

Antaredja : Lapor, siap untuk maju ke padang Kurusetra

Antaredja : Lapor, siap untuk maju ke padang KurusetraKresna : weleh weleh ngger tidak ada musuh yang dapat menandingi Dewa Kematian, karena dengan cicin Mustikabumi kamu akan hidup lagi begitu menyentuh bumi dengan kata lain kau tidak bisa mati dan hal itu akan mengacaukan rencana para Dewata perihal Perang Bharatajuda…bagaimana agar Pandawa menang kau gunakan aji Upasanta untuk menjilat telapak kakimu

Antareja : Lho iya AKU mati dong…..?

Kresna : Apa kamu tidak mau berkorban untuk Pendawa…?

Antareja : Oke, kau kan dewa Kehidupan, jadi nggak masalah kalau aku mati…nanti kau hidupkan aku lagi…he..he..

At his Mayesty request

It is time to go

It is time to go

Baca pula pembahasan

Jejak karir

Jendral A.H.Nasution

Karir

Karir

Atas campur tangan DPR dalam urusan intern Militer maka pada tanggal

17 October 1952, Nasution dan Simatupang melakukan show of force didepan

istana presiden dengan meriam Tank mengarah ke istana dan meminta agar

DPR dibubarkan

Presden Sukarno berhasil menghimbau baik tentara dan masyarakat untuk bubar .. akibatnya baik Nasution dan Simatupang dipecat dari dinas militer di bulan Desember 1952

Presden Sukarno berhasil menghimbau baik tentara dan masyarakat untuk bubar .. akibatnya baik Nasution dan Simatupang dipecat dari dinas militer di bulan Desember 1952

Pada tanggal 27 October 1955, Nasution di rehab ke posisi lamanya sebagai Kepala Staf Angkatan Darat

Jendral Ahmad Yani

Karir

Karir

Pasukannya berhasil menduduki Padang and Bukittinggi, dan untuk itu maka dipromosikan sebagai wakil 2 Kepala Staff Angkatan Darat pada tanggal 1 September 1962

Jendral Suharto

karir

karir

Menurut penulis buku The Smiling General (1969) OG. Roeder, Suharto was “well known for his tough, but not brutal, methods”.

Mari kita semua mengheningkan cipta bagi mereka yang telah berjasa bagi nusa dan bangsa

Benedict Anderson’s View of Nationalism

The child of late empire, who transformed the field of area studies, lived a life beyond boundaries.

In 1967, Sudisman, the

general secretary of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), whose ranks

had just been decimated in a series of massacres that left hundreds of

thousands dead, was put on trial. Of the top five PKI leaders, Sudisman

was the only one who appeared in court; the others were shot. Two

foreigners were always present in the Jakarta courtroom: Benedict

O’Gorman Anderson, a 30-year-old scholar of Indonesia, and Herbert

Feith, a colleague of Anderson’s from Australia.

Amid the parade of Communist witnesses, only two of them

spoke out in protest in the courtroom and refused to incriminate others.

One was an old woman who subsequently went mad; the other, Anderson

recalled many years later, “was this little Chinese kid who looked

nineteen or twenty. Very calmly, and with great dignity, he gave his

testimony. I was so impressed by it.”

Sudisman, who received a death sentence, also maintained

his composure. In 2001, Anderson told me that he “was so dignified, so

calm, and his speech was so great, that I felt a kind of moral

obligation” to do something: “As Sudisman was leaving the courtroom for

the last time, he looked at me and Herb. He didn’t say anything, but I

had such a strong feeling that he was thinking: ‘You have to help us.

Probably you two are the only ones I can trust to make sure that what I

said will survive.’ It was like an appeal from a dying man.” Anderson

answered that appeal in 1975, when he translated Sudisman’s speech into

English from a smuggled copy of the court transcript. A radical printing

collective in Australia published it as an orange-colored, 28-page

pamphlet titled “Analysis of Responsibility,” with an admiring

introduction by the translator.

After Sudisman’s trial, Anderson’s ability to do

research in Java would eventually be curtailed. The young scholar,

entirely fluent in Indonesian, was being watched: A US embassy document

from 1967 stated that Anderson was “regarded…as an outright Communist

or at least a fellow traveler.” He also found himself under attack in

the Indonesian press: The magazine Chas, which reportedly had

ties to the country’s intelligence services, called him a “useful idiot”

in a front-page article. In April 1972, Anderson was expelled from the

country. It was the beginning of an exile that would endure for almost

three decades.

With Indonesia closed to him, Anderson journeyed to

Bangkok in 1974. “It was a wonderful time to be there,” he later said. A

heady interlude between dictatorships allowed Thai radicalism to

flower. The good times ended in 1976, when the military overthrew the

civilian regime and publicly shot and hanged student radicals in

downtown Bangkok.

Still, the period Anderson spent in Thailand was

essential to his intellectual growth, as it forced him to think

comparatively—which, at the time, was rare among area-studies scholars.

“Being in Thailand,” he later said, “forced me to think all the time

about if I had to write about Thailand and Indonesia in one space, how

would I do it?” Anderson, who died in Batu, Indonesia, in December at

the age of 79, overcame that challenge, and the result was Imagined Communities (1983), a classic analysis of nationalism that has been translated into 29 languages.

* * *

In June 2001, when Anderson was 64, I traveled to upstate New York to profile him for Lingua Franca.

He lived in Freeville, eight miles east of Ithaca, in a spacious old

farmhouse surrounded by grazing cattle and with a barn topped by a

Javanese-style weather vane. For three days, we sat and talked in a

breezy kitchen packed with unruly stacks of crime novels, scholarly

journals, Asian newspapers, and doctoral theses. Mounted on a wall was a

striking black-and-white photograph of a youthful Sukarno, the

left-wing nationalist who led Indonesia to independence in 1949 and was

overthrown by General Suharto in 1967.

As I prepared to leave, I inquired if Anderson intended

to write a memoir, and he said no. But two years later, an editor at a

Japanese publishing house asked him for a small autobiographical volume.

“Embarrassed rejection” was his initial response: “Professors in the

West rarely have interesting lives. Their values are objectivity,

solemnity, formality and—at least officially—self-effacement.” But when a

special friend and former student, Kato Tsuyoshi, of Kyoto University,

agreed to assist him with the book and then translate it into Japanese,

Anderson consented. It was published, to his satisfaction, in Japan in

2009.

From the outset of the project, Benedict’s brother, the

historian and critic Perry Anderson, urged him to publish the memoir in

English, but he brushed the idea aside. In 2015, with his 80th birthday

approaching, he changed his mind. Shortly before his death, Anderson

completed the final draft of A Life Beyond Boundaries, which is

now before us. It’s a neat and tidy book about his unusual trajectory

and sensibility, infused with inside jokes, idiosyncratic asides, and

sly humor. It is also a tart overview of academic life. But mostly the

memoir is a primer for cosmopolitanism and an argument for traversing

geographical, historical, linguistic, and disciplinary borders.

The history of the Anderson family reads like a Conrad

novel. Benedict’s great-great-grandfather, along with a

great-great-uncle, joined the United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798, for

which they did time in prison. A nephew of theirs took part in the

uprising of 1848, and thereafter fled to Paris, Istanbul, and,

eventually, the United States, where he became a member of the New York

State Supreme Court. Another branch of the family tree has Anglo-Irish

landowners and military officers who served the British empire in Burma,

Afghanistan, Hong Kong, and India.

Anderson’s intrepid, linguistically gifted father spent

most of his career in China as an employee of the Chinese Maritime

Customs Service, which began as a tool of British and French

imperialists and, in his son’s words, was responsible for taxing

“imperial China’s maritime trade with the outside world.” Benedict was

born in Kunming in 1936, but his father made a consequential decision in

1941 to move the family to California: Had they remained in China, they

might have been imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp.

In 1945, the family moved to Ireland, where they lived

in a house full of “Chinese scrolls, pictures, clothes and costumes,

which we would often dress up in for fun.” The radio was another source

of entertainment and enlightenment: In the evenings, the family listened

to classic novels that were read aloud on the BBC by distinguished

actors, “so that our imaginations were filled with figures like Anna

Karenina, the Count of Monte Cristo, Lord Jim, Uriah Heep, Tess of the

D’Urbervilles, and so on.” In those years, traveling theater groups

proliferated in Ireland, and the Anderson children (including Benedict’s

sister Melanie) absorbed plays by Shakespeare, Shaw, Wilde, Sheridan,

and O’Casey.

His father died young, when Benedict was 9, and the

children were dispatched to boarding schools in England. His English

mother, who was passionate about books and ideas, was scraping by on a

pension, so Benedict had to win scholarships. He ended up garnering one

of 13 vacant slots at Eton, a place that immediately sharpened his sense

of class distinction. The scholarship boys lived in a separate dorm

from the sons of the British aristocracy and had to wear a special

“medieval” outfit. But he received an extraordinary old-fashioned

education in literature, art history, ancient history, archaeology, and

comparative modern history.

At the core of the curriculum was rigorous language

study in Latin, Greek, French, German, and a bit of “Cold War Russian.”

(Later, Anderson would learn Indonesian, Javanese, Thai, Tagalog, Dutch,

and Spanish.) The memorization and recitation of poems in Latin and

French were an essential aspect of his education; his teachers also

asked him to translate English poems into Latin and even to compose

poems in that language. Few students after him were educated in so

rigorous a fashion. It was the end of an era.

Having flourished at Eton, Anderson found Cambridge

University to be a tranquil holiday. He became enamored of film

(Japanese cinema, especially) and felt the first stirrings of

politicization. One afternoon during the Suez Crisis of 1956, he crossed

the campus and saw a group of brown-skinned students demonstrating:

Suddenly, out of the blue, the protestors were assaulted by a gang of big English student bullies, most of them athletes. They were singing “God Save the Queen!” To me this was incomprehensible, and reprehensible.

The protestors, mostly Indians and Ceylonese, were much smaller and thinner, and so stood no chance.… I tried to intervene to help them, only to have my spectacles snatched off my face and smashed in the mud.

After graduating from Cambridge, Anderson lingered at home

for six months, quarreling with his mother, who wanted him to become a

British diplomat. An alternative presented itself when a friend invited

him to work as a teaching assistant in Cornell University’s department

of government. He arrived in Ithaca during a snowstorm in January 1958

and stayed there for the duration of his long, productive career.

* * *

The 1950s and ’60s were heady years to be a graduate

student in Southeast Asian studies at Cornell: It and Yale were the only

American universities with robust programs in that area. Money was

plentiful, not only from the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, but also

from the US government, which was keen to understand peasant rebellions

and nationalist movements in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Anderson

savored the intellectual excitement of toiling in a new field: “students

felt like explorers investigating unknown societies and terrains.” His

peers—some of whom were from Burma, Vietnam, and Indonesia—literally

built the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, installing steel pillars to

reinforce the rotting floors of the abandoned frat house where the

program was located.

Some of the most pleasurable pages in A Life Beyond Boundaries

feature finely etched, affectionate portraits of Anderson’s mentors.

First among them was George Kahin, the savvy department chairman who was

a specialist in Indonesia’s late-1940s struggles for independence from

the Dutch, and whose sympathy for Indonesian nationalism would later

result in the temporary revocation of his passport during the McCarthy

years. Anderson writes that Kahin, who had participated in Quaker

activism in defense of Japanese-Americans in the 1940s, “formed me

politically.” Another influence was Claire Holt, a Russian-speaking Jew

from Latvia who, after working as a ballet critic in Paris and New York,

moved to Indonesia and became the lover of the German archeologist

Wilhelm Stutterheim, who shared her deep interest in Indonesia’s

precolonial civilizations. Holt had no scholarly credentials, but Kahin

brought her to Cornell to teach Indonesian languages to his graduate

students. Anderson spent countless hours in her house, absorbing her

extensive knowledge of traditional Javanese art, dance, and culture;

sometimes they would read Russian poetry aloud to each other. “Claire

Holt,” he writes, “was very special to me.”

Two other men, in the early days, were close to his

heart. Harry Benda was a Czech Jew whose business career in Java was

interrupted by the Japanese occupiers, who put him in an internment camp

that nearly ended his life. Later, Benda made his way to Cornell, where

he wrote a dissertation on the relationship between the Japanese and

Muslims in prewar and wartime Indonesia. John Echols was a “perfect

American gentleman” who knew a dozen languages and compiled the first

English-language Indonesian dictionary. Anderson’s adoration of

dictionaries derived from Echols: “Still today,” he writes, “the

favorite shelf in my personal library is filled only with dictionaries

of many kinds.”

Anderson was lucky not only in his mentors, but also in

the loose institutional arrangements at Cornell that cemented his

career: “Against normal recruitment rules—which require competitive

candidacies, extensive interviews, and hostility to ‘nepotism’—I walked

into an assistant professorship without any interviews and without any

outside candidate being considered.”

Kahin, his principal mentor, had urged Anderson to

undertake a dissertation on the Japanese occupation of Indonesia from

1942 to 1945, and the young scholar landed in Jakarta in December 1961.

His first glimpse of the country was unforgettable: “I remember vividly

the ride into town with all the taxi’s windows open. The first thing

that hit me was the smell—of fresh trees and bushes, urine, incense,

smoky oil lamps, garbage, and, above all, food in the little stalls that

lined most of the main streets.” He would remain in Indonesia for

almost two and a half years.

Jakarta was not yet a heaving, smog-filled megacity:

There were few cars, and the various neighborhoods still had a distinct

character. Foreigners were scarce. In contrast to the social hierarchies

Anderson had observed in the UK and Ireland, he was immediately struck

by the “egalitarianism” around him: He lived near a street where, after

dark, men would play chess on the sidewalks, and he noticed that clerks

and pedicab drivers would face off against high government officials and

debonair businessmen. For the young Anderson, this was “a kind of

social heaven.” The language came easily: His Indonesian took flight

after four months, and he found that “without self-consciousness, I

could talk happily with almost anyone—cabinet ministers, bus drivers,

military officers, maids, businessmen, waitresses, schoolteachers,

transvestite prostitutes, minor gangsters and politicians.” (His

connection to the language deepened with the years: Anderson told me

that he did much of his thinking in Indonesian.)

When Anderson wasn’t laboring in Jakarta’s archives, he

got to know Java, wandering through the old royal palaces; attending

performances of shadow plays and spirit possession; exploring the

Borobudur, the Buddhist stupa built in the 10th century (once he slept

till dawn on the stupa’s highest terrace “next to the Enlightened

Ones”); and visiting tiny villages of the interior.

From the evidence of this memoir, Anderson, lost in the

reveries of fieldwork and leisure, was largely unaware of the escalating

political frictions that would soon cause Java to explode.

* * *

On October 1, 1965, six Indonesian generals were

murdered and their bodies tossed down a well. The left-wing president,

Sukarno, was detained; General Suharto took control and blamed the coup

attempt on the PKI. It was the beginning of what Anderson would call

“the catastrophe”—a series of massacres that, according to a CIA study

from 1968, were comparable to the Soviet purges of the 1930s and the

Nazi mass murders of World War II.

Anderson and two colleagues (Ruth McVey and Frederick

Bunnell) observed these events from the safety of Ithaca. But they were

determined to provide an intellectual response to the Indonesian

calamity, and they immediately set out to prove that the official

account was flawed. Relying on a vast cache of provincial Indonesian

newspapers at Cornell, as well as Indonesian radio transcripts, the trio

produced, in January 1966, a 162-page report that became known as the

Cornell Paper.

The document, which took three months to write, insisted

that the coup attempt was not a Communist power grab, but an “internal

army affair” spearheaded by colonels from the province of Central Java.

Kahin, who was always keen to push US foreign policy in a more humane

direction, sent the Cornell Paper to Assistant Secretary of State

William Bundy, and it soon found its way to Joseph Kraft, a syndicated

columnist who disseminated the conclusions of the young Cornell

scholars.

In my discussions with Anderson in 2001, he defended the

main thrust of the Cornell Paper—that an intra-military dispute

triggered the violence—and he spoke with immense passion, and in

fascinating detail, about the events of 1965–66. Alas, much of what he

related to me is absent from A Life Beyond Boundaries.

The PKI, he explained, had a parliamentary orientation

that resembled the Italian Communist Party’s. In the early 1960s, he

admired its nationalism, its incorruptibility, and its opposition to the

Vietnam War. But the years had given him a clear-eyed sense of the

PKI’s errors. It was completely unarmed, but it embraced the rhetoric of

Maoism: “That was a huge mistake. It created fear and anxiety about the

Communist Party. It wasn’t a guerrilla army. That’s why they were

massacred; they were all out in the open.”

When the Indonesian government permitted Anderson to

return to the country in 1999, he attended a meeting of those who had

survived the terror of the 1960s. The meeting took place in a

nondescript Jakarta building owned by the Ministry of Manpower; most of

the attendees were elderly. He recalled it as “an incredibly

overwhelming experience,” akin to a Quaker meeting, where people talked

about their lives and experiences. When he took his seat, a buzz went

around the room; the foreign scholar was persuaded to speak. Afterward, a

dignified Chinese man who was around 50 approached him. Anderson

realized that before him was the “kid” who, 32 years earlier, had

challenged the judge at Sudisman’s trial in 1967. They spent a day

together and Anderson heard his tale, which he related to me:

Many of the Communists, when they were trying to escape the sweeps on them, fled into the Chinese ghettos, partly because the Chinese are much more closemouthed than the Indonesians are, partly because these ghettos are accustomed to a certain level of clandestinity. And this kid, who was a radical kid, was somehow recruited by Sudisman to be his personal courier in terms of contacting other people who were hiding underground.

Is the Cornell Paper a work of lasting scholarship? Anderson

insisted in 2001 that the events of October 1, 1965, were “manipulated

from the top by General Suharto,” whom he considered the puppet master

of the conspiracy. Contemporary scholars of the September 30th

Movement—or G30S, as the plotters were known—have a different view. In a

recent e-mail to me, University of British Columbia historian John

Roosa, the author of the 2006 study Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup D’État in Indonesia, noted:

I argued that Suharto knew about the plot beforehand but was not involved in it. From what is known I think it is clear that Suharto was not the mastermind. All Ben had was speculation. He speculated that Suharto, if not the mastermind, played the role of spoiler: Suharto had planted double-agents in the G30S group…who then sabotaged the plot, making sure that it committed an atrocity (killing the generals) and then collapsed. I think this is overreaching…. Ben also wanted to acquit the PKI of any involvement…. The argument of the Cornell Paper—Javanese officers acting on their own—is completely wrong.

According to Roosa, top PKI leaders, including the chairman,

D.N. Aidit, were deeply involved in the plot: “Aidit’s idea was to use

military personnel who were loyal to the PKI to get rid of the army

generals they suspected of being the key right-wing generals who were

promoting anticommunism.” But matters went awry: “The initial plan seems

to have been to capture the generals alive and present them to Sukarno,

but the plotters didn’t carry out the plan with much concern for

keeping the generals alive—three were shot or stabbed when they resisted

being abducted.”

Given Anderson’s emotional connection to these events,

one would expect that a memoir by him would contain a great deal about

the “catastrophe.” But the carnage is evoked fleetingly and from a

peculiar angle, in a brief passage about his comrade Pipit Rochijat

Kartawidjaja, an Indonesian exile and “eternal student” in Berlin who,

during the long Suharto dictatorship, clashed frequently and

successfully with the “small, corrupt” Indonesian consulate in Berlin,

effectively headed by an intelligence officer. Pipit, Anderson writes,

is “an amazingly gifted and fearless satirical writer” whose articles

are distinguished by “a mixture of formal Indonesian, Jakarta slang and

Low Javanese,” a style that incorporated “Javanese wayang-lore,

Sino-Indonesian kung-fu comic books, scatology and brazenly sexual jokes

to make his friends laugh their heads off.”

Anderson, who credits Pipit with teaching him how to

write fluently in Indonesian, translated one of his articles into

English, an essay entitled “Am I PKI… or Non-PKI?,” which was based on

incidents that Pipit had witnessed, as a young man, on a sugar estate in

East Java in 1965. Pipit’s essay was full of black humor, but, Anderson

says, “the horror haunted him”:

In his article he described how regular customers at the local brothel stopped going there when they saw the genitals of communists nailed to the door, and he recalled rafts piled high with mutilated corpses which floated down the Brantas river through the town of Kediri where he lived.

Writing at the end of his life, in a memoir that feels

post-ideological, Anderson chose to accentuate the halcyon days in

Java—the motorcycle trips through the interior, the sidewalk chess

games, the full moon over Borobudur—instead of the ruination of a

country he loved.

* * *

Anderson’s early work on Indonesia’s independence

struggle of the 1940s led him to think seriously about nationalism: He

saw how a skilled nationalist intelligentsia, based in Jakarta, had

summoned not only a nation called Indonesia but also a new language,

Indonesian, which became the language of resistance to the Dutch

colonial rulers. Imagined Communities also grew out of the

political realities in Southeast Asia following the Vietnam War. The

book emerged from what Anderson viewed, in the early 1980s, as a

“fundamental transformation in the history of Marxism and Marxist

movements”: the wars between Vietnam, Cambodia, and China in 1978–79.

Anderson simply couldn’t understand why Marxist regimes were fighting

each other instead of the Western imperialists. It was a worrying

spectacle: “I was haunted by the prospect of further full-scale wars

between the socialist states.”

Anderson began a comprehensive study of nationalism, a

force whose power and complexity were not explained by his sort of

Marxist theory. In writing Imagined Communities, he was partly inspired by Tom Nairn’s The Break-up of Britain

(1977), which, in Anderson’s words, had described the UK “as the

decrepit relic of a pre-national, pre-republican age and thus doomed to

share the fate of Austro-Hungary.” But Anderson strongly disagreed with

Nairn’s contention that “‘nationalism’ is the pathology of modern

developmental history, as inescapable as ‘neurosis’ in the individual.”

Anderson argued that nationalism was neither a pathology nor a fixed,

immutable force. Instead, he wrote, “it is an imagined political

community…because the members of even the smallest nation will never

know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet

in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.”

In an afterword to the 2006 edition of Imagined Communities,

Anderson reflected on the book’s enormous success: “In the 1980s it was

the only comparative study of nationalism’s history intended to combat

Eurocentrism, and making use of non-European language sources. It was

also the only one with a marked prejudice in favor of ‘small

countries’”—Hungary, Thailand, Switzerland, Vietnam, Scotland, and the

Philippines. Imagined Communities also broadly coincided with

the rise of theory in the academy: It attempted to combine, he wrote in

2006, “a kind of historical materialism with what later on came to be

called discourse analysis; Marxist modernism married to postmodernism

avant la lettre.”

Anderson says in the memoir that he wanted to provoke

his fellow scholars: “I deliberately brought together Tsarist Russia

with British India, Hungary with Siam and Japan, Indonesia with

Switzerland, and Vietnam with French West Africa…. These comparisons

were intended to surprise and shock, but also to ‘globalize’ the study

of the history of nationalism.”

What enabled him, in a learned fashion, to compare

Hungary with Japan was a cast of mind that was always wide-ranging,

endlessly curious, and interdisciplinary. When he surveys academic life,

he sees thick disciplinary walls that breed narrow, provincial

thinking. He tells us that, in his seminars on nationalism, he took

pleasure in making students look outside their cubby holes:

I forced the young anthropologists to read Rousseau, political scientists a nineteenth-century Cuban novel, historians Listian economics, and sociologists and literary comparativists Maruyama Masao. I picked Maruyama because he was a political scientist, an Asian/Japanese, and a very intelligent man who read in many fields and had a fine sense of humour and history. It was plain to me that the students had been so professionally trained that they did not really understand each other’s scholarly terminology, ideology or theory.

He was also determined to steer them clear of jargon-filled

writing, self-importance, and a reluctance (among American scholars) to

learn difficult foreign languages. On the whole, he finds academia much

too solemn, and likens professors to medieval monks determined to

eradicate “frivolity.” As a student at Cambridge, he filled his papers

with jokes, digressions, and sarcasm. In his early days at Cornell, he

was immediately informed that “scholarship is a serious

enterprise”—which made him reflect: “Now I understand what traditional

Chinese foot-binding must have felt like.”

* * *

Anderson survived a heart attack in 1996 and retired

from Cornell in 2001, after which he spent half of each year at his

apartment in a lower-middle-class district of Bangkok—a zone, he told

me, “full of small businesspeople, schoolteachers, mistresses of

policemen, this sort of thing.” Liberated from his teaching and

administrative duties, he threw himself into a number of projects: a

book about anarchism and anticolonial nationalisms, Under Three Flags

(which, he says, has “mystified many readers”); a literary-political

biography of Kwee Thiam Tjing, the Sino-Indonesian journalist and

columnist whose work, Anderson believed, embodied the finest qualities

of humanism and cosmopolitanism in early-20th-century Indonesia; and an

effort of “amateurish anthropology,” The Fate of Rural Hell: Asceticism and Desire in Buddhist Thailand. He never lost his passion for literature, and helped to translate Man Tiger

by the young Indonesian writer Eka Kurniawan, whose “novels and short

stories are in a class of their own, far above all authors in Southeast

Asia that I know,” and whose sensibility he compared to that of Gabriel

García Márquez.

He continued to think about nationalism, which is “a

powerful tool of the state and the institutions attached to it,” and

which, in nations ranging from China to Pakistan to Sri Lanka, is

“easily harnessed by repressive and conservative forces, which, unlike

earlier anti- dynastic nationalisms, have little interest in

cross-national solidarities.” He continued to reflect, too, on the fate

of the left:

For a long time, different forms of socialism—anarchist, Leninist, New Leftist, social-democratic—provided a ‘global’ framework in which a progressive, emancipationist nationalism could flourish. Since the fall of ‘communism’ there has been a global vacuum, partially filled by feminism, environmentalism, neo-anarchism and various other ‘isms,’ fighting in different and not always cooperative ways against the barrenness of neoliberalism and hypocritical ‘human rights’ interventionism. But a lot of work, over a long period of time, will be needed to fill the vacuum.

Anderson tells us that A Life Beyond Boundaries has

two principal themes: “The first is the importance of translation for

individuals and societies. The second is the danger of arrogant

provincialism, or of forgetting that serious nationalism is tied to

internationalism.” He was heartened by the fact that, in area studies,

many young Japanese are now learning Burmese; young Thais, Vietnamese;

and Filipinos, Korean. Such students, he says, “are beginning to see a

huge sky above them”:

It is important to keep in mind that to learn a language is not simply to learn a linguistic means of communication. It is also to learn the way of thinking and feeling of a people who speak and write a language which is different from ours. It is to learn the history and culture underlying their thoughts and emotions and so to learn to empathize with them.

His memoir concludes with a coda about memory, technology,

and poetry, in which his prime target is Google: “Google is an

extraordinary ‘research engine,’ says Google, without irony in its use

of the word ‘engine,’ which in Old English meant ‘trickery’ (as is

reflected in the verb ‘to engineer’) or even ‘an engine of torture.’”

Anderson frets that future generations may never know the actual feel of

a book: “Japanese books are bound one way, Burmese books another.”

Groupthink rules: “The faith students have in Google is almost

religious.”

As a student, he was enthralled by the cadence and

rhymes of poems he had memorized, such as Rimbaud’s “dizzying ‘Le Bateau

ivre.’” Today, search has supplanted memorization: “One effect of ‘easy

access to everything’ is the acceleration of a trend that I had already

noticed long before Google was born: there is no reason to remember anything, because we can retrieve ‘anything’ by other means.”

The poems he memorized in his youth stayed with him

always. In 2007, he was invited to Leningrad to assist with a class on

nationalism for young teachers in Russian provincial universities.

Addressing them, he remembered some Russian from his days at Eton and

proceeded to recite the final stanza of a poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky,

who perished, amid murky circumstances, in Moscow in 1930. To his

astonishment, all of the students joined with him:

Shine always,“I was in tears by the end,” recalls Anderson. “Some of the students, too.”

Shine everywhere,

To the depth of the last day!

Shine—

And to hell with everything else!

That’s my motto—

And the sun’s!

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar